Between hot things, sharp things, and spinny things, there’s more than enough danger in the average hacker’s shop to maim and mutilate anyone who fails to respect their power. But somehow lasers don’t seem to earn the same healthy fear, which is strange considering permanent blindness can await those who make a mistake lasting mere fractions of a second.

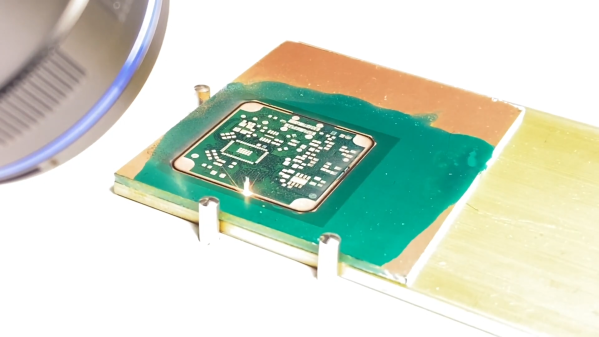

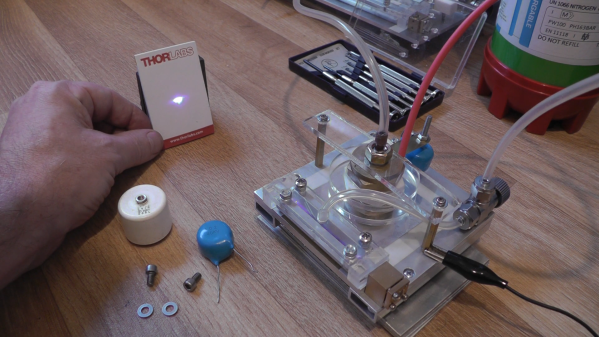

To avoid that painful fate, high-power laser fan [Brainiac75] undertook building a beam dump, which is a safe place to aim a laser beam in an experimental setup. His version has but a few simple parts: a section of extruded aluminum tubing, a couple of plastic end caps, and a conical metal plumb bob. The plumb bob gets mounted to one of the end caps so that its tip points directly at a hole drilled in the center of the other end cap. The inside and the outside of the tube and the plumb bob are painted with high-temperature matte black paint before everything is buttoned up.

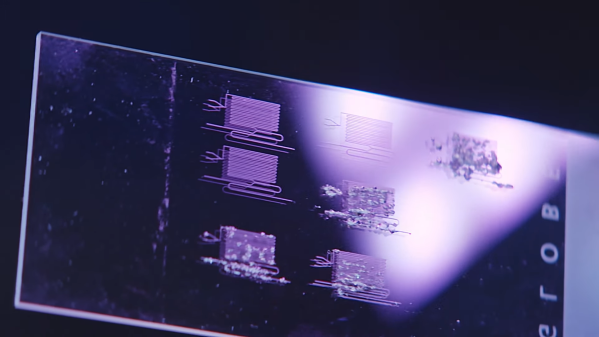

In use, laser light entering the hole in the beam dump is reflected off the surface of the plumb bob and absorbed by the aluminum walls. [Brainiac75] tested this with lasers of various powers and wavelengths, and the beam dump did a great job of safely catching the beam. His experiments are now much cleaner with all that scattered laser light contained, and the work area is much safer. Goggles still required, of course.

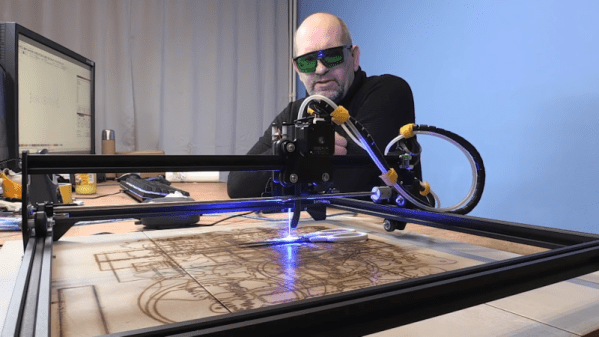

Hats off to [Brainiac75] for an instructive video and a build that’s cheap and easy enough that nobody using lasers has any excuse for not having a beam dump. Such a thing would be a great addition to the safety tips in [Joshua Vasquez]’s guide to designing a safe laser cutter.

Continue reading “Beam Dump Makes Sure Your Laser Path Is Safely Terminated”