This month DietPi released version 8.12 of this SBC-oriented Linux distribution. Most notable is the addition of support for the NanoPi R6S and the Radxa ROCK 5B SBCs. The ROCK 5B features the new flagship Rockchip RK3588 SoC with quad Cortex-A76 and quad Cortex-A55. What makes DietPi interesting as an operating system for not just higher end SBCs but also lower-end SBCs compared to options like Debian, Raspberry Pi OS and Armbian is that it has a strong focus on being the most optimized. This translates in a smaller binary size, lower RAM usage and more optimized performance.

The DietPi setup experience is as straightforward as with the aforementioned options, except that right from the bat you get provided with many more options to tweak. While the out of the box experience and hitting okay on the provided defaults is likely to be already more than satisfactory for most users – with something like the optional graphical interface easy to add – enterprising users can tweak details about the hardware, the filesystem and more.

When we set up DietPi on a Raspberry Pi Zero, it definitely feels like a much more light-weight experience than the current Debian Bullseye-based Raspberry Pi OS. Even though DietPi is also based on Debian, it leaves a lot more RAM and storage space free, which is a definite boon when running on a limited platform like a Raspberry Pi Zero. Whether it’s polite to state in public or not, DietPi definitely rubs in that many standard SBC images are rather pudgy these days.

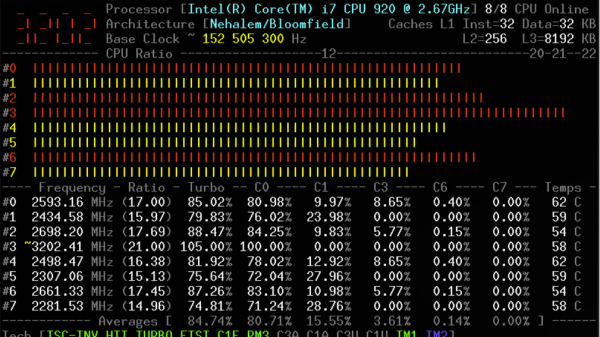

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.

The tool relies on a kernel module, and is coded primarily in C, with some assembly code used to measure performance as accurately as possible. It’s capable of reporting everything from core frequencies to details on hyper-threading and turbo boost operation. Other performance reports include information on instructions per cycle or instructions per second, and of course, all the thermal monitoring data you could ask for. It all runs in the terminal, which helps keep overheads low.