Although there is a lot of discussion about health care problems in big countries like the United States, we often don’t realize that this is a “first world” problem. In many places, obtaining health care of any kind can be a major problem. In places where water and electricity are scarce, a lot of modern medical technology is virtually unobtainable. A team from Standford recently developed a cheap, easily made centrifuge using little more than paper, scrap material like wood or PVC pipe, and string.

A centrifuge is a device that spins samples to separate them and–to be effective–they need to spin pretty fast. Go to any medical lab in a developed country and you’ll find at least one. It will be large, heavy, expensive, and it will require electricity. Some have tried using hand-operated centrifuges using mechanisms like an egg beater or a salad spinner, but these don’t really move fast enough to work well. At the least, it takes a very long time to get results with a slow centrifuge.

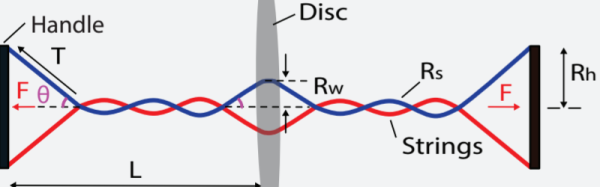

[M. Saad Bhamla] and his colleagues at Stanford started brainstorming on this problem. They thought about toys that rotate, including a yo-yo. Turns out, those don’t spin all that fast, either. Then they considered a whirligig. We had forgotten what those are, but it is the real name for a toy that has a spinning disk and (usually) a string. When you pull on the string, the disk spins and the more you pull, the faster the disk spins. These actually have an ancient origin appearing in medieval tapestries and almost 2,500 years ago in China.

[Bhamla] found that how the toy worked was poorly understood (from a scientific standpoint) and took pictures of one in operation with a high-speed camera. The team was able to create the “paperfuge”, a human-powered centrifuge that would spin at 125,000 RPM, enough to separate plasma from blood in under two minutes and isolate malaria parasites in 15. Some versions of the device could cost as little as twenty cents and don’t require anything more exotic than paper and string. You can see a video about the paperfuge, below.

Continue reading “Paper Toy Can Save Lives” →