Until about lunch time, the coffee goes pretty fast in our office. Only a few of us drink it well into the afternoon, though, and it’s anyone’s guess how long the coffee’s been sitting around when we need a 4:00 pick-me-up. It would be great to install a coffee timer like [Paul]’s Brewdoo to keep track of these things.

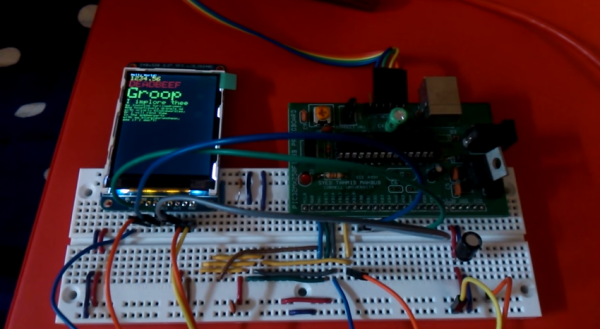

The Brewdoo’s clean and simple design makes it easy for anyone in the office to use. [Paul]’s office has two carafes, so there’s a button, an RGB LED, and a line on the LCD for each. Once a pot is brewed, push the corresponding button and the timer is reset. The RGB LED starts at green, but turns yellow and eventually red over the course of an hour. Brewdoo has a failsafe in place, too: if a timer hasn’t been reset for four hours, its LED turns off and the LCD shows a question mark.

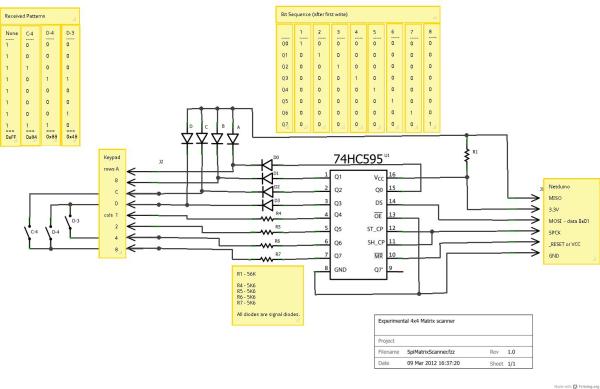

[Paul] knew he couldn’t touch the existing system since his company leases the equipment, so the Brewdoo lives in an enclosure that [Paul] CNC’d with custom g-code and affixed to the brewing machine with hard drive magnets. Although [Paul] designed it with an Arduino Uno for easy testing and code modification, the Brewdoo has a custom PCB with a ‘328P. The code, Fritzing diagram and Eagle files are up at [Paul]’s GitHub.