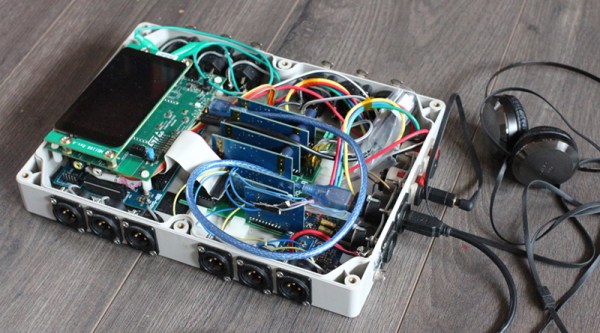

Field recorders, or backpackable audio recorders with a few XLR jacks and an SD card slot, are a niche device, and no matter what commercial field recorder you choose you’ll always compromise on what features you want versus what features you’ll get. [Ben Biles] didn’t feel like compromising so he built his own multichannel audio DSP field recorder. It has a four channel balanced master outputs, with two stereo headphone outputs, eight or more inputs, digital I/O, and enough routing for multitrack recording.

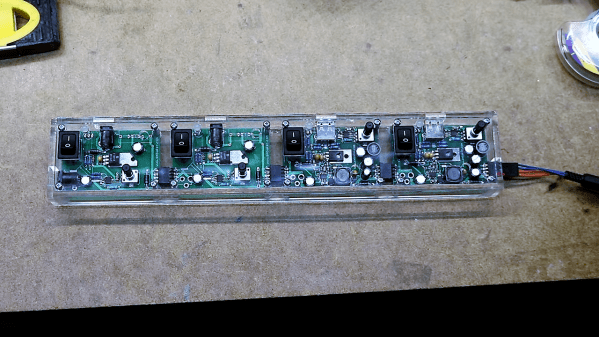

Mechanically, the design of the system is a 3D printed box studded on every side with various connectors and patch points. This is what you get when you want a lot of I/O, and yep, those are panel mount connectors so get ready to pony up on the price of your connectors. The analog front end is a backplane sort of thing on a piece of perfboard, containing an eight channel differential I/O.

Of course any audio recorder is awful to use unless there’s a great user interface, and for that you can’t get any better than a high-resolution touchscreen on a phone. This led [Ben] to use Bluetooth to connect to an app showing the gain, levels, a toggle for phantom power, and a checkbox for line or microphone. If that’s not enough there are also some MIDI knobs for volume, because MIDI is still great for user input. It’s everything you want in a portable recording rig, and yes, there is a soundcloud demo. You can also check out a demo video below.

Continue reading “The Multichannel Field Recorder You Can Build Right Now”