In many people’s memories, Snake lived and breathed on Nokia handsets from the late 90s and early 2000s. However, the game has been around for much longer than that, and will continue to live on in the future. That’s at least in part thanks to people like [Hari Wiguna] keeping it alive by implementing it on new platforms.

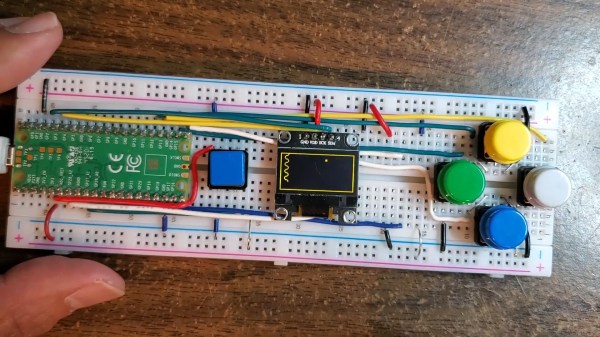

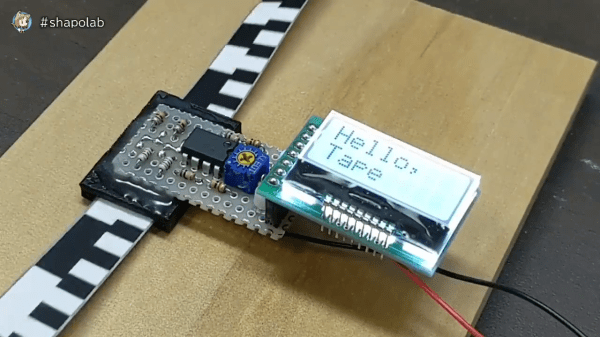

[Hari] set about writing Snake in MicroPython for the Raspberry Pi Pico. The hardware side of things is simple enough – five buttons hooked up to the Pico, along with an 128×64 I2C OLED screen to display the game on. On the software side of things, [Hari] pushed the boat out, deciding that his version of Snake had to have the player character slither like the real thing. This took a little effort to get right, particularly when navigating corners in different directions. However, perseverance paid off and [Hari] got the job done.

Code is on GitHub for those that want to tinker at home. It’s a tidy piece of work, though not the weirdest place we’ve seen the game appear – we’ve actually seen it run within PCB routing software before thanks to some nifty scripting. Video after the break. Continue reading “Play Your Favorite Nokia Game On The Raspberry Pi Pico”