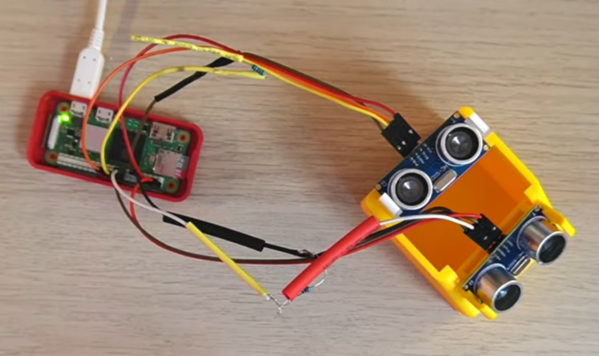

[Stanislaw Pusep] has gifted us with the Pianolizer project – an easy-to-use toolkit for music exploration and visualization, an audio spectrum analyzer helping you turn sounds into piano notes. You can run his toolkit on a variety of different devices, from Raspberry Pi and PCs, to any browser-equipped device including smartphones, and use its note output however your heart desires. To show off his toolkit in action, he set it up on a Raspberry Pi, with Python code taking the note data and sending color information to the LED strip, displaying the notes in real time as he plays them on a MIDI keyboard! He also created a browser version that you can use with a microphone input or an audio file of your choosing, so you only need to open a webpage to play with this toolkit’s capabilities.

He took time to make sure you can build your projects with this toolkit’s help, providing usage instructions with command-line and Python examples, and even shared all the code used in the making of the demonstration video. Thanks to everything that he’s shared, now you can add piano note recognition to any project of yours! Pianolizer is a self-contained library implemented in JavaScript and C++ (which in turn compiles into WebAssembly), and the examples show how it can be used from Python or some other language.

[Stanislaw] also documented the principles behind the code, explaining how the note recognition does its magic in simple terms, yet giving many insights. We are used to Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) being our go-to approach for spectral analysis, aka, recognizing different frequencies in a stream of data. However, a general-purpose FFT algorithm is not as good for musical notes, since intervals between note frequencies become wider as frequency increases, and you need to do more work to distinguish the notes. In this toolkit, he used a Sliding Discrete Fourier Transform (SDFT) algorithm, and explains to us how he derived the parameters for it from musical note frequencies. In the end of the documentation, he also gives you a lot of useful references if you would like to explore this topic further!

What are you going to build with this? Maybe, a box that records you playing the flute and instantly turns it into sheet music? Or, perhaps, an AI that continues the song for you when you stop?

Continue reading “Pianolizer Helps Your Musical Projects Distinguish Notes”