Early in the morning of February 24th, Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, a professor at California’s Middlebury Institute of International Studies watched Russia’s invasion of Ukraine unfold in realtime with troop movements overlaid atop high-resolution satellite imagery. This wasn’t privileged information — anybody with an internet connection could access it, if they knew where to look. He was watching a traffic jam on Google Maps slowly inch towards and across the Russia-Ukraine border.

As he watched the invasion begin along with the rest of the world, another, less-visible facet of the emerging war was beginning to unfold on an ill-defined online battlefield. Digital espionage, social media and online surveillance have become indispensable instruments in the tool chest of a modern army, and both sides of the conflict have been putting these tools to use. Combined with civilian access to information unlike the world has ever seen before, this promises to be a war like no other.

Modern Cyberwarfare

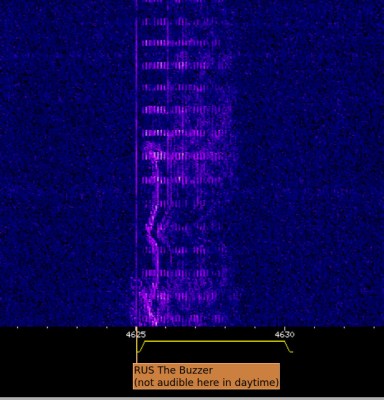

The first casualties in the online component of the war have been websites. Two weeks ago, before the invasion began en masse, Russian cyberwarfare agents launched distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against Ukrainian government and financial websites. Subsequent attacks have temporarily downed the websites of Ukraine’s Security Service, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and government. A DDoS attack is a relatively straightforward way to quickly take a server offline. A network of internet-connected devices, either owned by the aggressor or infected with malware, floods a target with request, as if millions of users hit “refresh” on the same website at the same time, repeatedly. The goal is to overwhelm the server such that it isn’t able to keep up and stops replying to legitimate requests, like a user trying to access a website. Russia denied involvement with the attacks, but US and UK intelligence services have evidence they believe implicates Moscow. Continue reading “The Invisible Battlefields Of The Russia-Ukraine War”