Chemical engineers at MIT have pulled off something that was once thought impossible. By polymerizing material in two different directions at once, they have created a polymer that is very strong. You can read a pre-print version of the paper over on Arxiv.

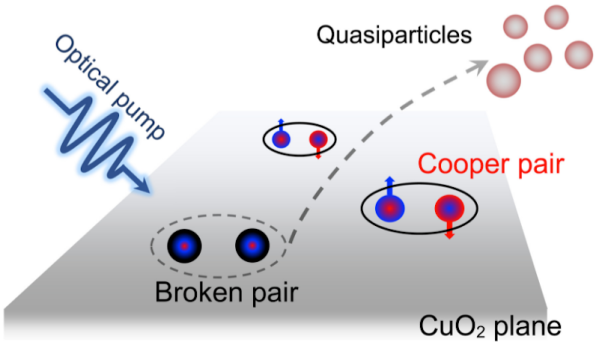

Polymers owe many of their useful properties to the fact that they make long chains. Molecules known as monomers join together in strings held together by covalent bonds. Polymer chains may be cross-linked which changes its properties, but it has long been thought that material that had chains going through the X and Y axis would have desirable properties, but making these reliably is a challenge.

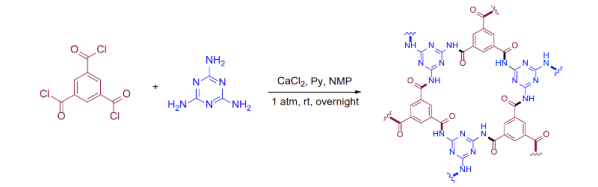

Part of the problem is that it is hard to line up molecules, even large monomers. If one monomer in the chain rotates a bit, it will create a defect in the 2D structure and that defect will grow rapidly as you add more monomers. The new technique is relatively easy to do and is irreversible which is good because reversible chains tend to have undesirable characteristics like low chemical stability. Synthesis does require a few chemicals like melamine, calcium chloride, pyridine, and trimesic acid. Along with N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone, the mixture eventually forms a gel. The team took pieces of gel and soaked it in ethanol. With some filtering, ultrasonics, centrifuging, and washing with water and acetone, the material was ready for vacuum drying and was made into a powder.

The powder is dissolved in acid and placed on a spinning silicon wafer to form a polymerized nanofilm. Other 2D films have been produced, of course, such as graphene, but polymer films may have a number of applications. In particular, in contrast to conventional polymers, sheets of this material are impermeable to gas and liquid, which could make it very useful as a coating.

According to the MIT press release, the film’s elastic modulus is about four and six times greater than that of bulletproof glass. The amount of force required to break the material is about twice that of steel. It doesn’t sound like this material will be oozing out of our 3D printers anytime soon. But maybe one day you’ll be able to get 2D super-strong resin.

For all their faults, conventional polymers changed the world as we know it. Some polymers occur naturally, and some use natural ingredients, too.