Not so long ago, it was hard to fly. Forget actual manned aircraft and pilots licenses; even flying model aircraft required hours of practice, often under the tutelage of a master at a flying field. But along with that training came an education in the rules of safe flight, including flying at a designated airfield and watching out for obstacles.

We accidentally messed that up. We in the drone industry made aircraft super easy to fly — perhaps too easy to fly. Thanks to smart autopilots and GPS, you can open a box, download an app and press “take off”. The copter will dutifully rise into the air and wait there for further instructions — no skill required. And it will do this even if you happen to be in an NFL football stadium in the middle of a big game. Or near an airport. Or in the midst of a forest fire.

The problem is that along with taking training out of the process of flying a drone, we inadvertently also took out the education process of learning about safe and responsible flight. Sure, we drone manufacturers include all sorts of warning and advisories in our instructions manual (which people don’t read) and our apps (which they swipe past), and companies such as DJI and my own 3DR include basic “geofencing” restrictions to try to keep operators below 400 feet and within “visual line of sight”. But it’s not enough.

Every day there are more reports of drone operators getting past these restrictions and flying near jetliners, crashing into stadiums, and interfering with first responders. So far it hasn’t ended in tragedy, but the way things are going it eventually will. And in the meantime, it’s making drones increasingly controversial and even feared. I call this epidemic of (mostly inadvertent) bad behavior “mass jackassery”. As drones go mass market, the odds of people doing dumb things with them reach the singularity of certainty.

We’ve got to do something about this before governments do it for us, with restrictions that catch the many good uses of drones in the crossfire. The reality is that most drone operators who get in trouble aren’t malicious and may not even know that what they’re doing is irresponsible or even illegal. Who can blame them? It’s devilishly hard to understand the patchwork quilt of federal, state and local regulations and guidelines, which change by the day and even the hour based on “airspace deconfliction” rules and FAA alerts written for licensed pilots and air traffic control. Many drone owners don’t even know that such rules exist.

Drones Themselves Should Know Rules of Each Area

Fortunately, they don’t have to. Our drones can be even smarter — smart enough to know where they should and shouldn’t fly. Because modern drones are connected to phones, they’re also connected to the cloud. Every time you open their app, that app can check online to find appropriate rules for flight where you are, right then and there.

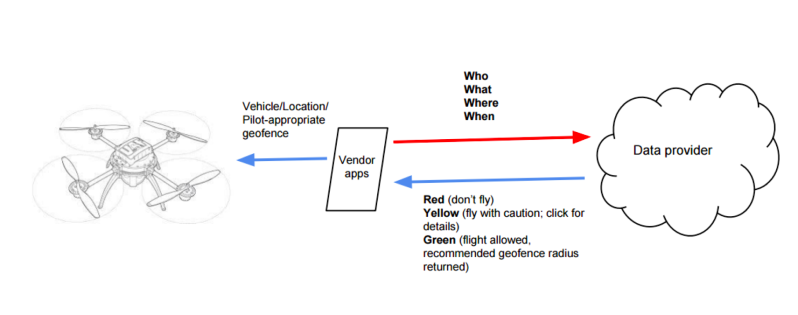

Here’s how it works. The app sends four data fields to a cloud service: Who (operator identifier), What (aircraft identifier), Where (GPS and altitude position) and When (either right now or a scheduled time in the case of autonomous missions). The cloud service then returns a “red light” (flight not allowed), a “green light” (flight allowed, with basic restrictions such as a 400 feet altitude ceiling), or “yellow light” (additional restrictions or warnings, which can be explained to the operator in context and at the point of use).

Right now industry groups such as the Dronecode Foundation, the Small UAV Coalition (I help lead both of them, but this essay just reflects my own personal views) and individual manufacturers such as 3DR and DJI are working on these “safe flight” standards and APIs. Meanwhile, a number of companies such as Airmap and Skyward are building the cloud services to provide the up-to-date third-party data layer that any manufacturer can use. It will start with static no-fly zone data such as proximity to airports, US national parks and other banned airspace such as Washington DC. But it will quickly add dynamic data, too, such as forest fires, public events, and proximity to other aircraft.

(For more on this, you can read a white paper from one of the Dronecode working groups here and higher level description here.)

There’s Always a Catch

Of course, this system isn’t perfect. It’s only as good as the data it uses, which is still pretty patchy worldwide, and the ways that the manufacturers implement those restrictions. Some drone makers may choose to treat any area five miles from an airport as a hard ban and prohibit all flight in that zone, even at the cost of furious customers who had no idea they were five miles from an airport when they bought that toy at Wal-mart (nor do they think it should matter, since it’s just a “toy”). Other manufacturers may choose to make a more graduated restriction for the sake of user friendliness, adding a level of nuance that is not in the FAA regulation. They might ban, say, flight one mile from an airport, but only limit flight beyond that to something like 150ft of altitude (essentially backyard-level flying).

That’s a reasonable first step. But the ultimate safe flight system would go a lot further. It would essentially extend the international air traffic control system to millions of aircraft (there are already a million consumer drones in the air) flown by everything from children to Amazon. The only way to do that is to let the drones regulate themselves (yes, let Skynet become self-aware).

Peer-to-peer Air Traffic Control

There’s a precedent for such peer-to-peer air traffic control: WiFI. Back in the 1980s, the FCC released spectrum in the 2.4 Ghz band for unlicensed use. A decade later, the first 802.11 standards for Wifi were released, which was based on some principles that have application to drones, too.

- The airspace used is not otherwise occupied by commercial operators

- The potential for harm is low (in the case of WiFi, low transmission power. In the case of drones, low kinetic energy due to the weight restrictions of the “micro” category)

- The technology has the capability to self-”deconflict” the airspace by observing what else is using it and picking a channel/path that avoids collisions.

That “open spectrum” sandbox that the FCC created also created a massive new industry around WiFi. It put wireless in the hands of everyone and routed around the previous monopoly owners of the spectrum, cellphone carriers and media companies. The rest was history.

We can do the same thing with drones. Let’s create an innovation “sandbox” with de minimus regulatory barriers for small UAVs flying within very constrained environments. The parameters of the sandbox could be almost anything, as long as they’re clear, but it should be kinetic energy and range based (a limit of 2kg and 20m/s at 100m altitude and 1,000m range within visual line of sight would be a good starting point).

We can do the same thing with drones. Let’s create an innovation “sandbox” with de minimus regulatory barriers for small UAVs flying within very constrained environments. The parameters of the sandbox could be almost anything, as long as they’re clear, but it should be kinetic energy and range based (a limit of 2kg and 20m/s at 100m altitude and 1,000m range within visual line of sight would be a good starting point).

As in the case of open spectrum, in relatively low risk applications, such as micro-drones, technology can be allowed to “self-deconflict the airspace” without the need for monopoly exclusions such as exclusive licences or regulatory permits. How? By letting the drones report their position using the same cellphone networks they used to get permission to fly in the first place. The FAA already has a standard for this, called ADS-B, which is based on transponders in each aircraft reporting their position. But those transponders are expensive and unnecessary for small drones, which already know their position and are connected to the cloud. Instead, they can use “virtual ADS-B” to report their position via their cell network connections, and that data can be injected into the same cloud data services they used to check if their flight was safe in the first place.

Once this works, we’ll have a revolution. What WiFi did the telecoms industry, autonomous, cloud-connected drones can do to the aerospace industry. We can occupy the skies, and do it safely. Technology can solve the problems it creates.

About the Author

Chris Anderson (@Chr1sa) is the CEO of 3D Robotics and founder of DIY Drones. From 2001 through 2012 he was the Editor in Chief of Wired Magazine. Before Wired he was with The Economist for seven years in London, Hong Kong and New York.

Chris Anderson (@Chr1sa) is the CEO of 3D Robotics and founder of DIY Drones. From 2001 through 2012 he was the Editor in Chief of Wired Magazine. Before Wired he was with The Economist for seven years in London, Hong Kong and New York.

The author of the New York Times bestselling books The Long Tail and Free as well as the Makers: The New Industrial Revolution.

His background is in science, starting with studying physics and doing research at Los Alamos and culminating in six years at the two leading scientific journals, Nature and Science.

In his self-described misspent youth [Chris] was a bit player in the DC punk scene and amusingly, a band called REM. You can read more about that here.

Awards include: Editor of the Year by Ad Age (2005). Named to the “Time 100,” the newsmagazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world (2007). Loeb Award for Business Book of the Year (2007). Wired named Magazine of the Decade by AdWeek for his tenure (2009). Time Magazine’s Tech 40 — The Most Influential Minds In Technology (2013). Foreign Policy Magazine’s Top 100 Global Thinkers (2013).

We can do the same thing with drones. Let’s create an innovation “sandbox” with de minimus regulatory barriers for small UAVs flying within very constrained environments. The parameters of the sandbox could be almost anything, as long as they’re clear, but it should be kinetic energy and range based (a limit of 2kg and 20m/s at 100m altitude and 1,000m range within visual line of sight would be a good starting point).

We can do the same thing with drones. Let’s create an innovation “sandbox” with de minimus regulatory barriers for small UAVs flying within very constrained environments. The parameters of the sandbox could be almost anything, as long as they’re clear, but it should be kinetic energy and range based (a limit of 2kg and 20m/s at 100m altitude and 1,000m range within visual line of sight would be a good starting point). Chris Anderson (

Chris Anderson (

![Image Credit: [Rupunzell] on EEVBlog](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/eevblogrupunzel.jpg?w=400)