It never fails. Lay down some kind of superlative — fastest, cheapest, smallest — around this place and someone out there says, “Hold my beer” and gets to work. In this case, it’s another, even simpler audio oscillator, this time with just a loudspeaker and a battery.

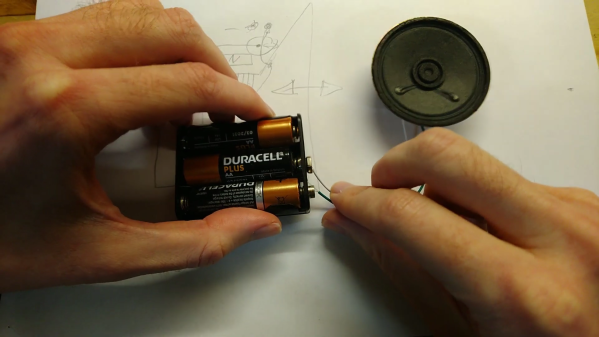

Attentive readers will recall the previous title holder was indeed pretty simple, consisting only of the mic and speaker from an old landline telephone handset wired in series with a battery. Seeing this reminded [Hydrogen Time] of a lucky childhood accident while experimenting with a loudspeaker, which he recreates in the video below. The BOM for this one is even smaller than the previous one — just a small speaker and a battery, plus a small scrap of solid hookup wire. The wire is the key; rather than connecting directly to the speaker terminal, it connects to the speaker frame on one end while the other is carefully adjusted to just barely touch the flexible wire penetrating the speaker cone on its way to the voice coil.

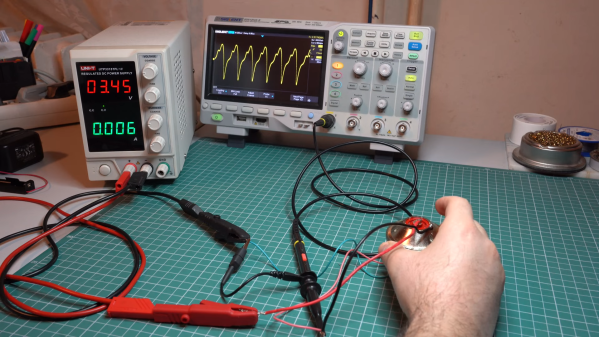

When power is applied with the correct polarity, current flows through the wire into the voice coil, which moves the cone and breaks the circuit. The speaker’s diaphragm resets the cone, completing the circuit and repeating the whole process. The loudspeaker makes a little click with each cycle, leading to a very rough-sounding oscillator. [Hydrogen Time] doesn’t put a scope on it, but we suspect the waveform would be a ragged square wave whose frequency depends on the voltage, the spring constant of the diaphragm, and the spacing between the fixed wire and the voice coil lead.

Yes, we realize this is stretching the definition of an audio oscillator somewhat, but you’ve got to admit it’s simple. Can you get it even simpler?

Continue reading “Simplest Speaker Oscillator, Now Even Simpler”