“LEDs improve everything.” Words to live by. Most everything that Debra Ansell of [GeekMomProjects] makes is bright, bold, and blinky. But if you’re looking for a simple string of WS2812s, you’re barking up the wrong tree. In the last few years, Debra has been making larger and more complicated assemblies, and that has meant diving into the mechanical design of modular PCBs. In the process Debra has come up with some great techniques that you’ll be able to use in your own builds, which she shared with us in a presentation during the 2021 Hackaday Remoticon.

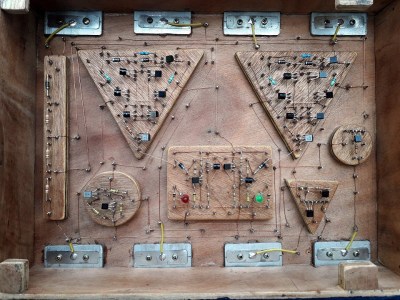

She starts off with a quick overview of the state of play in PCB art, specifically of the style that she’s into these days: three dimensional constructions where the physical PCB itself is a sculptural element of the project. She’s crossing that with the popular triangle-style wall hanging sculpture, and her own fascination with “inner glow” — side-illuminated acrylic diffusers. Then she starts taking us down the path of creating her own wall art in detail, and this is where you need to listen up. Continue reading “Remoticon 2021 // Debra Ansell Connects PCB In Ways You Didn’t Expect”

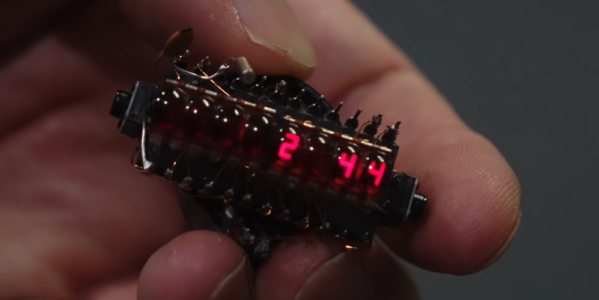

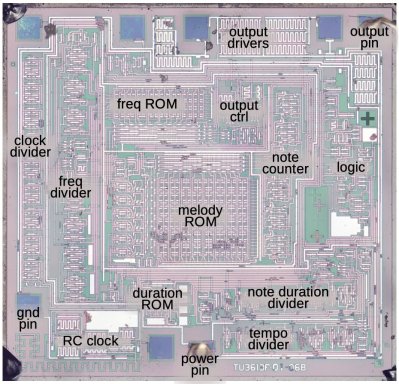

The surprise in this age of ubiquitous microcontrollers is that this is not a smart device; instead it’s a single-purpose logic chip whose purpose is to step through a small ROM containing note values and durations, driving a frequency generator to produce the notes themselves. The frequency generator isn’t the divider chain from the RC oscillator that we might expect, instead it’s a shift register arrangement which saves on the transistor count.

The surprise in this age of ubiquitous microcontrollers is that this is not a smart device; instead it’s a single-purpose logic chip whose purpose is to step through a small ROM containing note values and durations, driving a frequency generator to produce the notes themselves. The frequency generator isn’t the divider chain from the RC oscillator that we might expect, instead it’s a shift register arrangement which saves on the transistor count.