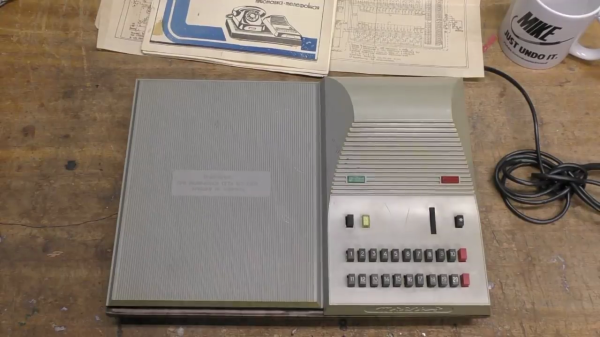

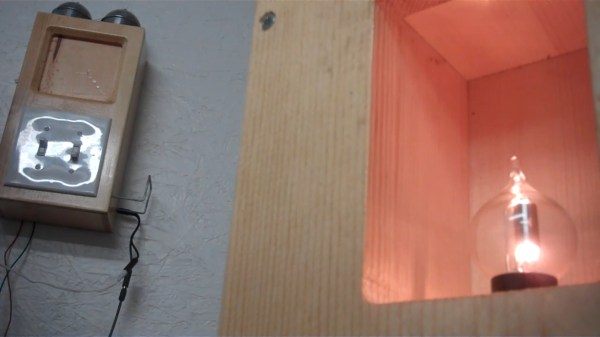

If you thought programming your 1990s VCR was rough, wait until you see this Russian telephone autodialer that [Mike] took apart over on the mikeselectricalstuff YouTube channel (video below the break). [Mike] got this 1980s Soviet-era machine a few years ago, and finally got around to breaking into it to learning what makes it tick. The autodialer plugs into the phone line, much like an old-school answering machine. It provides the user with 40 pre-set telephone numbers, arranged in two banks of 20, and a speaker to monitor the connection process. It uses pulse dialing — no touch tones. What’s surprising is how you program the numbers. Given that this was build in the 1980s Soviet Union, he wasn’t expecting a microcontroller. But he wasn’t expecting transformer core “rope” memory, either.

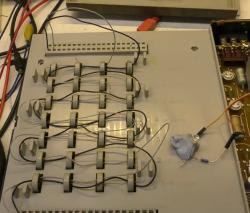

The phone normally sits on a platform on the left side of the machine. Raising up the platform exposes a bank of toroidal cores, arranged in seven rows of four. Each row corresponds to a dialed digit, and the four cores used to encode a single digit. At the top and bottom of the programming board are two 40-pin connectors, each pin corresponding to one of the preset phone numbers. A bunch of patch wires would have been provided, and you program each number by threading a long wire through the appropriate cores, connecting it at the top and bottom connectors much like a modern solderless breadboard. It’s also interesting to see the components and construction technique of this circuit board. For example, the diodes have the strip on the Anode end, not the cathode as we’re normally used to today. The transistor cans are mounted upside down like dead spiders.