When the RTL2832-based USB digital TV sticks were revealed to have hidden capabilities that made the an exceptionally cheap software-defined radio receiver, it was nothing short of a game-changing moment for the home radio experimenter. The RTL might not be the best radio available, but remains a pretty good deal for only $10 from your favourite online supplier.

Having bought your RTL SDR, you will soon find yourself needing a few accessories. A decent antenna perhaps, an HF upconverter, and maybe an attenuator. To help you, [IgrikXD] has come up with a repository containing open-source implementations of all those projects and more. There’s an HF upconverter handily in both SMD and through-hole versions, as well as a wideband active antenna. A resonant antenna for a single band will always out-perfom a wideband device if your interest lies on only one frequency, but when your receiver has such a wide range as that of the RTL it’s irresistible to look further afield so the wideband antenna is a useful choice.

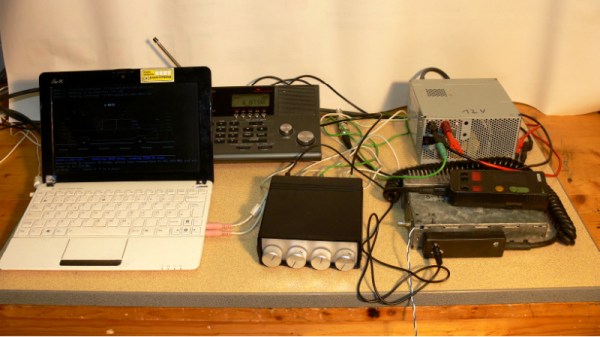

The RTL SDR is a device that just keeps on giving, and has featured innumerable times here since since its first appearance a few years ago. Whether you are into passive radar or using it to decode data from RF-equipped devices it’s the unit of choice, though we rather like it as a piece of inexpensive test equipment.

Via Hacker News.

Header image: Joeceads [CC BY-SA 4.0].