What kind of clever things could you do with a signal that had a period of 2 hours? Or 20? Any ideas? No seriously, tell us. Because [Joseph Eoff] has come up with a way to produce incredibly low frequency signals that stretch out for hours, and we’d love to figure out what we can do with it.

To be fair, it’s not like [Joseph] has any ideas either. He thought it would be an interesting project, and figures now that he has the technology, maybe some application will come to him. They say that if you’ve got a hammer everything looks like a nail, so maybe the next project he sends our way will be a sinusoidal fish feeder.

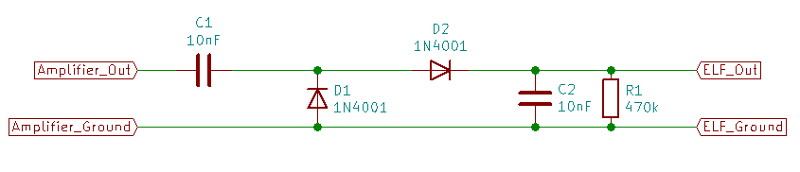

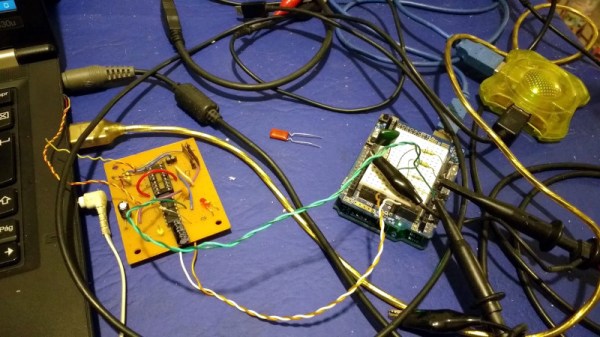

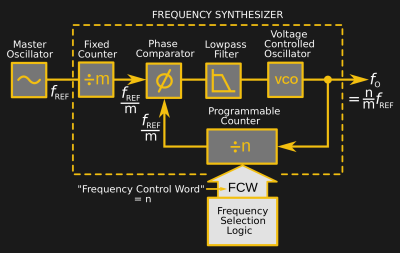

[Joseph] says doing the software side of things with Pure Data wasn’t a problem, but getting it out of the computer proved to be tricky. It turns out that your average computer sound card isn’t equipped to handle frequencies down into the millihertz range (big surprise), so they need to be coaxed out with some extra hardware. Using a simple circuit not unlike an AM demodulator, he’s able to extract the low-frequency signal from a 16 kHz carrier.

So if you ever find yourself in need of a handful of hertz, now you’ve got the tool to generate them. At least it’s more practical than how they used to generate low frequency signals back in the 1900s.