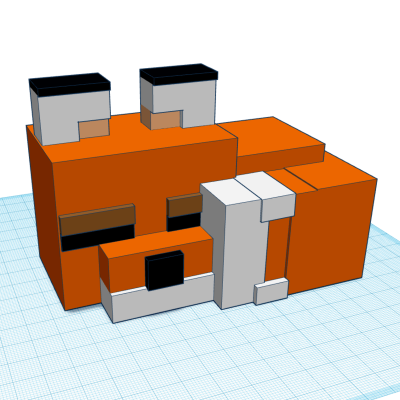

Summer break has started over here, and my son went off to his first of a few day-camp-like activities last week. It was actually really cool – a workshop held by our local Fablab where they have the kids make a Minecraft building and then get to 3D-print it out. He loves playing and building in Minecraft, so we figured this would be right up his alley.

I had naively thought that it would work something like this: the kids build something in Minecraft, and then some software extracts the build and converts it into an STL file. Makes sense, because they already are more-or-less fluent in Minecraft modelling. And as I thought about that, it was a pretty clever idea.

But the truth was even sneakier. They warmed up by making something in Minecraft, then they opened up TinkerCAD, which was new to all of the kids, and built a 3D model there. Then they converted the TinkerCAD models into Minecraft, and played with what they had just built while the 3D printers hummed away.

The kids didn’t even flinch at having to learn a new 3D modelling tool, and the parallels to what they were already comfortable doing in Minecraft were obvious to them. My son came home and told me how much easier it was to do your 3D modelling in “this other Minecraft” – he meant TinkerCAD – because you don’t need to build everything out of single blocks. He thought he was playing games, but he’d secretly used his first CAD tool. Nice trick!

Then I look back and realize how much I must have learned about computers through playing as a kid. Heck, how much I still learn through playing. And of course I’m not alone – that’s one of the things that shines through in a large number of the projects we feature. Hack on and have fun!