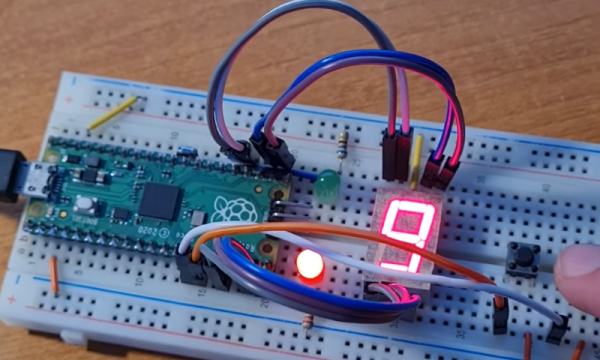

Ever want to play with an FPGA, but don’t have the hardware? Now, if you have one of those ever-abundant Pi Picos, you can start playing with Verilog without getting an FPGA board. The FakePGA project by [tvlad1234], based on the Verilator toolkit, provides you with a way to compile Verilog into C++ for the RP2040. FakePGA even integrates RP2040 GPIOs so that they work as digital pins for the simulated GPIOs, making it a significant step up from computer-aided FPGA code simulation

[tvlad1234] provides instructions for setting this up with Linux – Windows, though untested, could theoretically run this through WSL. Maximum clock speed is 5KHz – not much, but way better than not having any hardware to test with. Everything you’d want is in the GitHub repo – setup instructions, Verilog code requirements, and a few configuration caveats to keep in mind.

We cover a lot of projects where FPGAs are used to emulate hardware of various kinds, from ISA cards to an entire Game Boy. CPU emulation on FPGAs is basically the norm — it’s just something easy to do with the kind of power that an FPGA provides. Having emulation in the opposite direction is unusual, though, we’ve seen FPGAs being emulated with FPGAs, so perhaps it was inevitable after all. Of course, if you have neither a Pico nor an FPGA, there’s always browser based emulators.