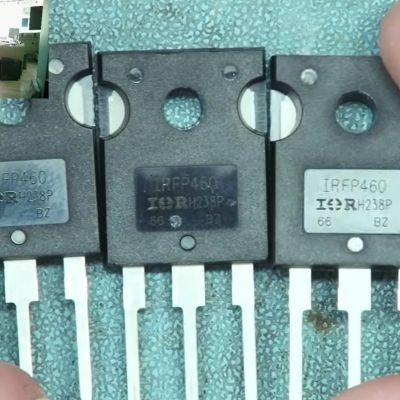

These days, it’s super-easy to jump onto the World Wide Web to find purported replacement parts using nothing but the part identifier, whether it’s from a reputable source like Digikey or Mouser or from more general digital fleamarkets like eBay and AliExpress. It’s hardly a secret that many of the parts you can buy online via fleamarkets are not genuine. That is, the printed details on the package do not match the actual die inside. After AliExpress-sourced MOSFETs blew in a power supply repair by [Learn Electronics Repair], he first tried to give the MOSFETs the benefit of the doubt. Using an incandescent lightbulb as a current limiter, he analyzed the entire PSU circuit before putting the blame on the MOSFETs (IRFP460) and ordering new ones from LCSC.

Buying from a distributor instead of a marketplace means you can be sure the parts are from the manufacturer. This means that when a part says it is a MOSFET with specific parameters, it almost certainly is. A quick component tester session showed the gate threshold of the LCSC-sourced MOSFETs to be around 3.36V, while that of the AliExpress ‘IRFP460’ parts was a hair above 1.8V, giving a solid clue that whatever is inside the AliExpress-sourced MOSFETs is not what the package says it should be.

Unsurprisingly, after fitting the PSU with the two LCSC-sourced MOSFETs, there was no more magic smoke, and the PSU now works. The lesson here is to be careful buying parts of unknown provenance unless you like magic smoke and chasing weird bugs.

Continue reading “Comparing AliExpress Vs LCSC-Sourced MOSFETs”