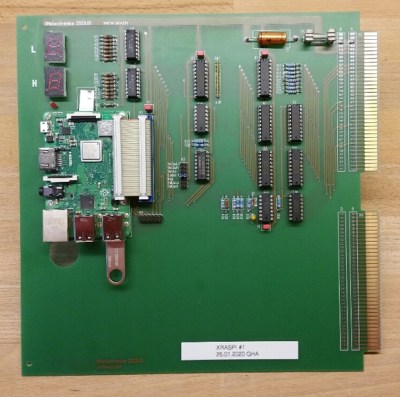

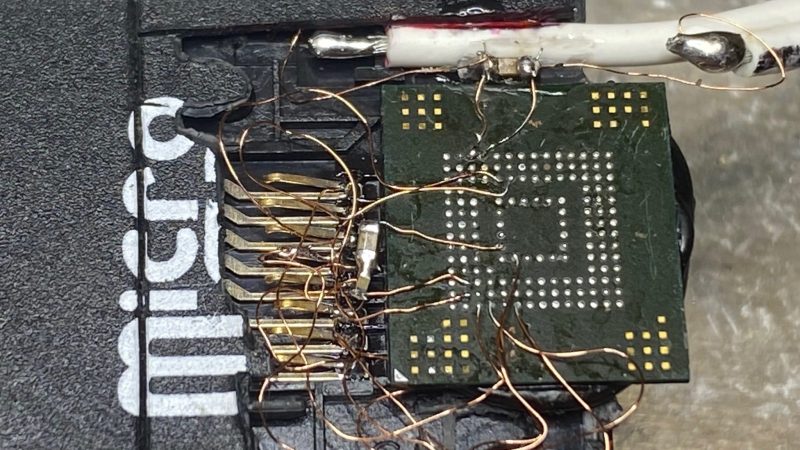

A lot of old technology runs on parts no longer produced – HDDs happen to be one such part, with IDE drives specifically being long out of vogue, and going extinct to natural causes. There’s substitutes, but quite a few of them are either wonky or require expensive storage medium. Now, [dosdude1] has turned his attention to 1.8 ZIF IDE SSDs – FFC-connected hard drives that are particularly rare and therefore expensive to replace, found in laptops like the Macbook Air 1,1 2008 model. Unsatisfied with substitutes, he’s designed an entire SSD from the ground up around an IDE SSD controller and NAND chips. Then, he made the design open-source and filmed an assembly video so that we can build our own. Take a look, we’ve put it below the break!

For an open-source design, there’s a respectable amount of work shared with us. He’s reverse-engineered some IDE SSDs based on the SM2236 controller to design the schematic, and put the full KiCad files on GitHub. In the video, he shows us how to assemble this SSD using only a hot air station and a soldering iron, talks about NAND matching and programming software intricacies, and shows the SSD working in the aforementioned Macbook Air. Certainly, assembly would have been faster and easier with a stencil, but the tools used work great for what’s a self-assembly tutorial!

Continue reading “ZIF HDDs Dying Out? Here’s An Open-Source 1.8″ SSD”