Another week of ransomware, and this time it’s the beef market that’s been shut down, due to a crippling infrastructure attack out of Russia — but hold up, it’s not that simple. Let’s cover the facts. Some time on Sunday, May 30, JBS USA discovered a ransomware attack against their systems. It seems that their response team did exceptionally well, pulling the plug on affected machines, and starting recovery right away. By Wednesday, it was reported that most of their operations were back in action.

Continue reading “This Week In Security: Ransomware, WeLock, And Amazon Arbitration”

Security Hacks1542 Articles

This Week In Security: M1RACLES, The Full Half-Double, And Patch Gaps

We occasionally make fun of new security vulnerabilities that have a catchy name and shiny website. We’re breaking new ground here, though, in covering a shiny website that makes fun of itself. So first off, this is a real vulnerability in Apple’s brand-new M1 chip. It’s got CVE-2021-30747, and in some very limited cases, it could be used for something malicious. The full name is M1ssing Register Access Controls Leak EL0 State, or M1RACLES. To translate that trying-too-hard-to-be-clever name to English, a CPU register is left open to read/write access from unprivileged userspace. It happens to be a two-bit register that doesn’t have a documented purpose, so it’s perfect for smuggling data between processes.

Do note that this is an undocumented register. If it turns out that it actually does something important, this vulnerability could get more serious in a hurry. Until then, thinking of it as a two-bit vulnerability seems accurate. For now, however, the most we have to worry about is that two processes can use this to pass information back and forth. This isn’t like Spectre or Rowhammer where one process is reading or writing to an unrelated process, but both of them have to be in on the game.

Do note that this is an undocumented register. If it turns out that it actually does something important, this vulnerability could get more serious in a hurry. Until then, thinking of it as a two-bit vulnerability seems accurate. For now, however, the most we have to worry about is that two processes can use this to pass information back and forth. This isn’t like Spectre or Rowhammer where one process is reading or writing to an unrelated process, but both of them have to be in on the game.

The discoverer, [Hector Martin], points out one example where this could actually be abused: to bypass permissions on iOS devices. It’s a clever scenario. Third party keyboards have always been just a little worrying, because they run code that can see everything you type, passwords included. The long-standing advice has been to never use such a keyboard, if it asks for network access permissions. Apple has made this advice into a platform rule — no iOS keyboards get network access. What if a device had a second malicious app installed, that did have Internet access permissions? With a covert data channel, the keyboard could shuffle keystrokes off to its sister app, and get your secrets off the device.

So how much should you care about CVE-2021-30747? Probably not much. The shiny site is really a social experiment to see how many of us would write up the vulnerability without being in on the joke. Why go to the hassle? Apparently it was all an excuse to make this video, featuring the appropriate Bad Apple!! music video.

Half-Double’ing Down on Rowhammer

A few days ago, Google announced the details of Half-Double, and the glass is definitely Half-Double full with all the silly puns that come to mind. The concept is simple: If Rowhammer works because individual rows of ram are so physically close together, does further miniaturization enable attacks against bits two rows away? The answer is a qualified yes.

Quick refresher, Rowhammer is an attack first demonstrated against DDR3 back in 2014, where rapid access to one row of memory can cause bit-flip errors in the neighboring row. Since then, there have been efforts by chip manufacturers to harden against Rowhammer, including detection techniques. At the same time, researchers have kept advancing the art through techniques like Double-Sided Rowhammer, randomizing the order of reads, and attempts to synchronize the attack with the ram’s refresh intervals. Half-Double is yet another way to overcome the protections built into modern ram chips.

We start by specifying a particular ram row as the victim (V). The row right beside it will be the near aggressor row (N), and the next row over we call the far aggressor row (F). A normal Rowhammer attack would simply alternate between reading from the near aggressor and a far-off decoy, rapidly toggling the row select line, which degrades the physical charge in neighboring bits. The Half-Double attack instead alternates between the far aggressor and a decoy row for 1000 cycles, and then reads from the near aggressor once. This process is repeated until the victim row has a bit flip, which often happens within a few dozen iterations. Because the hammering isn’t right beside the victim row, the built-in detection applies mitigations to the wrong row, allowing the attack to succeed in spite of the mitigations.

More Vulnerable Windows Servers

We talked about CVE-2021-31166 two weeks ago, a wormable flaw in Windows’ http.sys driver. [Jim DeVries] started wondering something as soon as he heard about the CVE. Was Windows Remote Management, running on port 5985, also vulnerable? Nobody seemed to know, so he took matters into hiis own hands, and confirmed that yes, WinRM is also vulnerable to this flaw. From what I can tell, this is installed and enabled by default on every modern Windows server.

I finally found time to answer my own question. WinRM *IS* vulnerable. This really expands the number of vulnerable systems, although no one would intentionally put that service on the internet.

— Jim DeVries (@JimDinMN) May 19, 2021

And far from his optimistic assertion that surely no-one would expose that to the Internet… It’s estimated that there over 2 million IPs doing just that.

More Ransomware

On the ransomware front, there is an interesting story out of The Republic of Ireland. The health system there was hit by Conti ransomware, and the price for decryption set at the equivalent of $20 million. It came as a surprise, then, when a decryptor was freely published. There seems to be an ongoing theme in ransomware, that the larger groups are trying to manage how much attention they draw. On the other hand, this ransomware attack includes a threat to release private information, and the Conti group is still trying to extort money to prevent it. It’s an odd situation, to be sure.

Inside Baseball for Security News

I found a series of stories and tweets rather interesting, starting with the May Android updates at the beginning of the month. [Liam Tung] at ZDNet does a good job laying out the basics. First, when Google announced the May Android updates, they pointed out four vulnerabilities as possibly being actively exploited. Dan Goodin over at Ars Technica took umbrage with the imprecise language, calling the announcement “vague to the point of being meaningless”.

Shane Huntley jumped into the fray on Twitter, and hinted at the backstory behind the vague warning. There are two possibilities that really make sense here. The first is that exploits have been found for sale somewhere, like a hacker forum. It’s not always obvious if an exploit has indeed been sold to someone using it. The other possibility given is that when Google was notified about the active exploit, there was a requirement that certain details not be shared publicly. So next time you see a big organization like Google hedge their language in an obvious and seemingly unhelpful way, it’s possible that there’s some interesting situation driving that language. Time will tell.

The Patch Gap

The term has been around since at least 2005, but it seems like we’re hearing more and more about patch gap problems. The exact definition varies, depending on who is using the term, and what product they are selling. A good working definition is the time between a vulnerability being public knowledge and an update being available to fix the vulnerability.

There are more common reasons for patch gaps, like vulnerabilities getting dropped online without any coordinated disclosure. Another, more interesting cause is when an upstream problem gets fixed and publicly announced, and it takes time to get the fix pulled in. The example in question this week is Safari, and a fix in upstream WebKit. The bug in the new AudioWorklets feature is a type confusion that provides an easy way to do audio processing in a background thread. When initializing a new worker thread, the programmer can use their own constructor to build the thread object. The function that kicks off execution doesn’t actually check that it’s been given a proper object type, and the object gets cast to the right type. Code is executed as if it was correct, usually leading to a crash.

The bug was fixed upstream shortly after a Safari update was shipped. It’s thought that Apple ran with the understanding that this couldn’t be used for an actual RCE, and therefore hadn’t issued a security update to fix it. The problem there is that it is exploitable, and a PoC exploit has been available for a week. As is often the case, this vulnerability would need to be combined with at least one more exploit to overcome the security hardening and sandboxing built into modern browsers.

There’s one more quirk that makes this bug extra dangerous, though. On iOS devices, when you download a different browser, you’re essentially running Safari with a different skin pasted on top. As far as I know, there is no way to mitigate against this bug on an iOS device. Maybe be extra careful about what websites you visit for a few days, until this get fixed.

This Week In Security: Watering Hole Attackception, Ransomware Trick, And More Pipeline News

In what may be a first for watering hole attacks, we’ve now seen an attack that targeted watering holes, or at least water utilities. The way this was discovered is a bit bizarre — it was found by Dragos during an investigation into the February incident at Oldsmar, Florida. A Florida contractor that specializes in water treatment runs a WordPress site that hosted a data-gathering script. The very day that the Oldsmar facility was breached, someone from that location visited the compromised website.

You probably immediately think, as the investigators did, that the visit to the website must be related to the compromise of the Oldsmar treatment plant. The timing is too suspect for it to be a coincidence, right? That’s the thing, the compromised site was only gathering browser fingerprints, seemingly later used to disguise a botnet. The attack itself was likely carried out over Teamviewer. I will note that the primary sources on this story have named Teamviewer, but call it unconfirmed. Assuming that the breach did indeed occur over that platform, then it’s very unlikely that the website visit was a factor, which is what Dragos concluded. On the other hand, it’s easy enough to imagine a scenario where the recorded IP address from the visit led to a port scan and the discovery of a VNC or remote desktop port left open. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Watering Hole Attackception, Ransomware Trick, And More Pipeline News”

PSA: Amazon Sidewalk Rolls Out June 8th

Whether you own any Amazon surveillance devices or not, we know how much you value your privacy. So consider this your friendly reminder that Amazon Sidewalk is going live in a few weeks, on June 8th. A rather long list of devices have this setting enabled by default, so if you haven’t done so already, here’s how to turn it off.

Don’t know what we’re talking about? Our own Jenny List covered the topic quite concretely a few months back. The idea behind it seems innocent enough on the surface — extend notoriously spotty Wi-Fi connectivity to devices on the outer bounds of the router’s reach, using Bluetooth and LoRa to talk between devices and share bandwidth. Essentially, when Amazon flips the switch in a few weeks, their entire fleet of opt-in-by-default devices will assume a kind of Borg hive-mind in that they’ll be able to share connectivity.

A comprehensive list of Sidewalk devices includes: Ring Floodlight Cam (2019), Ring Spotlight Cam Wired (2019), Ring Spotlight Cam Mount (2019), Echo (3rd Gen), Echo (4th Gen), Echo Dot (3rd Gen), Echo Dot (4th Gen), Echo Dot (3rd Gen) for Kids, Echo Dot (4th Gen) for Kids, Echo Dot with Clock (3rd Gen), Echo Dot with Clock (4th Gen), Echo Plus (1st Gen), Echo Plus (2nd Gen), Echo Show (1st Gen), Echo Show (2nd Gen), Echo Show 5, Echo Show 8, Echo Show 10, Echo Spot, Echo Studio, Echo Input, Echo Flex. — Amazon Sidewalk FAQ

Now this isn’t a private mesh network in your castle, it’s every device in the kingdom. So don’t hesitate, don’t wait, or it will be too late. Grab all your Things and opt-out if you don’t want your doorbell cam or Alexa machine on the party line. If you have the Alexa app, you can allegedly opt out on all your devices at once.

Worried that Alexa is listening to you more often than she lets on? You’re probably right.

This Week In Security: Fragattacks, The Pipeline, Codecov, And IPv6

Some weeks are slow, and the picking are slim when discussing the latest security news. This was not one of those weeks.

First up is Fragattacks, a set of flaws in wireless security protocols, allowing unauthenticated devices to inject packets into the network, and in some cases, read data back out. The flaws revolve around 802.11’s support for packet aggregation and frame fragmentation. The whitepaper is out, so let’s take a look.

Fragmentation and aggregation are techniques for optimizing wireless connections. Packet aggregation is the inclusion of multiple IP packets in a single wireless frame. When a device is sending many small packets, it’s more efficient to send them all at once, in a single wireless frame. On the other hand, if the wireless signal-to-noise ratio is less than ideal, shorter frames are more likely to arrive intact. To better operate in such an environment, long frames can be split into fragments, and recombined upon receipt.

There are a trio of vulnerabilities that are built-in to the wireless protocols themselves. First up is CVE-2020-24588, the aggregation attack. To put this simply, the aggregation section of a wireless frame header is unauthenticated and unencrypted. How to exploit this weakness isn’t immediately obvious, but the authors have done something clever.

There are a trio of vulnerabilities that are built-in to the wireless protocols themselves. First up is CVE-2020-24588, the aggregation attack. To put this simply, the aggregation section of a wireless frame header is unauthenticated and unencrypted. How to exploit this weakness isn’t immediately obvious, but the authors have done something clever.

First, for the purposes of explanation, we will assume that there is already a TCP connection established between the victim and an attacker controlled server. This could be as simple as an advertisement being displayed on a visited web page, or an image linked to in an email. We will also assume that the attacker is performing a Man in the Middle attack on the target’s wireless connection. Without the password, this only allows the attacker to pass the wireless frames back and forth unmodified, except for the aggregation header data, as mentioned. The actual attack is to send a special IP packet in the established TCP connection, and then modify the header data on the wireless frame that contains that packet.

When the victim tries to unpack what it believes to be an aggregated frame, the TCP payload is interpreted as a discrete packet, which can be addressed to any IP and port the attacker chooses. To put it more simply, it’s a packet within a packet, and the frame aggregation header is abused to pop the internal packet out onto the protected network. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Fragattacks, The Pipeline, Codecov, And IPv6”

Apple AirTag Spills Its Secrets

The Apple AirTag is a $29 Bluetooth beacon that sticks onto your stuff and helps you locate it when lost. It’s more than just a beeper though, the idea is that it can be silently spotted by any iDevice — almost like a crowd-sourced mesh network — and its owner alerted of its position wherever they are in the world.

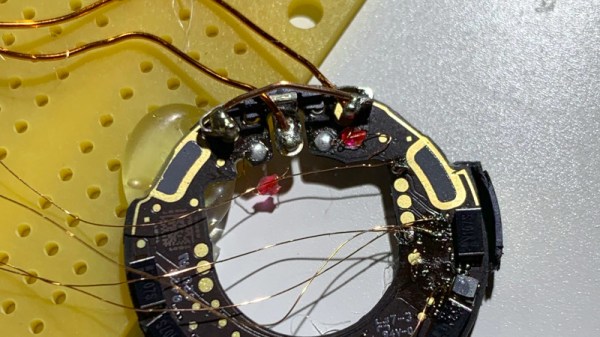

There are so many questions about its privacy implications despite Apple’s reassurances, so naturally it has been of great interest to those who research such things. First among those working on it to gain control of its nRF52832 microcontroller is [Stacksmashing], who used a glitching technique whereby the chip’s internal power supply is interrupted with precise timing, to bypass the internally enabled protection of its debug port. The firmware has been dumped, and of course a tag has been repurposed for the far more worthwhile application of Rickrolling Bluetooth snoopers.

The idea of a global network of every iDevice helping reunite owners with their lost possessions is on the face of it a very interesting one, and Apple are at great pains on the AirTag product page to reassure customers about the system’s security. On one hand this work opens up the AirTag as a slightly expensive way to get an nRF microcontroller for other applications, but the real value will come as the firmware is analysed to see how at the tag itself works.

[Stacksmashing] has appeared on these pages many times before, often in the context of Nintendo hardware. Just one piece of work is the guide to opening up a Nintendo Game and Watch.

A Dutch City Gets A €600,000 Fine For WiFi Tracking

It’s not often that events in our sphere of technology hackers have ramifications for an entire country or even a continent, but there’s a piece of news from the Netherlands (Dutch language, machine translation) that has the potential to do just that.

Enschede is an unremarkable but pleasant city in the east of the country, probably best known to international Hackaday readers as the home of the UTwente webSDR and for British readers as being the first major motorway junction we pass in the Netherlands when returning home from events in Germany. Not the type of place you’d expect to rock a continent, but the news concerns the city’s municipality. They’ve been caught tracking their citizens using WiFi, and since this contravenes Dutch privacy law they’ve been fined €600,000 (about $723,000) by the Netherlands data protection authorities.

The full story of how this came to pass comes from Dave Borghuis (Dutch language, machine translation) of the TkkrLab hackerspace, who first brought the issue to the attention of the municipality in 2017. On his website he has a complete timeline (Dutch, machine translation), and in the article he delves into some of the mechanics of WiFi tracking. He’s at pains to make the point that the objective was always only to cause the WiFi tracking to end, and that the fine comes only as a result of the municipality’s continued intransigence even after being alerted multiple times to their being on the wrong side of privacy law. The city’s response (Dutch, machine translation) is a masterpiece of the PR writer’s art which boils down to their stating that they were only using it to count the density of people across the city.

The events in Enschede are already having a knock-on effect in the rest of the Netherlands as other municipalities race to ensure compliance and turn off any offending trackers, but perhaps more importantly they have the potential to reverberate throughout the entire European Union as well.