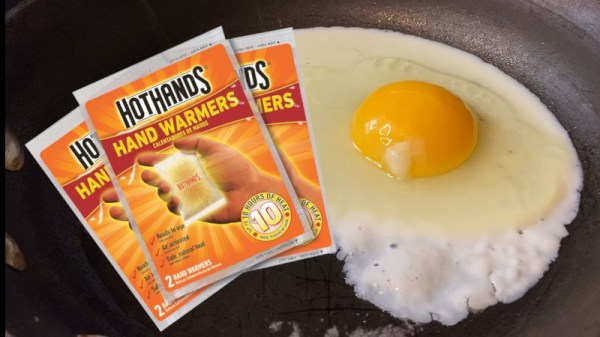

Handwarmers are great to keep your fingers functional in icy weather, but can they do more? [Greg] wondered if they could be put to good use cooking an egg, and got down to work.

The handwarmers in question are the HotHands brand, based on an iron chemistry. The warmers create their heat from the exothermic reaction between iron and oxygen that creates rust. Thus, these handwarmers need plenty of airflow to heat up. To enable this, [Greg] 3D printed a small crate with plenty of vents, into which he stacked six hand warmer sachets. An egg was nestled in the center – a perfect choice as it can be cooked in its own packaging. The pile reached temperatures of 160 F and was able to maintain that level for an hour, important as egg proteins tend to start coagulating and denaturing around 150 F. Once removed, [Greg] hoped to find a solid egg, but instead was rewarded with a somewhat gooey, semi-solid result instead. Regardless, the egg had reached an elevated temperature and shown some signs of cooking, and as [Greg] appears to be still putting out videos, we’ll assume he hasn’t yet died of salmonella.

We’d love to see this turn into an engineering competition, though, with prizes for the best cooked egg with the least amount of handwarmers. We’ve featured other egg cooking apparatus before, too. Video after the break.