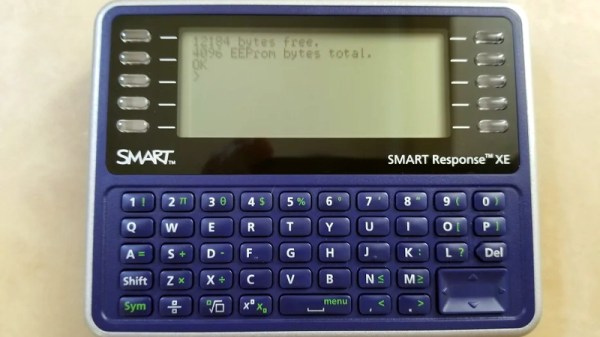

Ever since the SMART Response XE was brought to our attention back in 2018, we’ve been keeping a close lookout for projects that make use of the Arduino-compatible educational gadget. Admittedly it’s taken a bit longer than we’d expected for the community to really start digging into the capabilities of the QWERTY handheld, but occasionally we see an effort like this port of BASIC to the SMART Response XE by [Dan Geiger] that reminds us of why we were so excited by this device to begin with.

This project combines the SMART Response XE support library by [Larry Bank] with Tiny BASIC Plus, which itself is an update of the Arduino BASIC port by [Michael Field]. The end result is a fun little BASIC handheld that has all the features and capabilities you’d expect, plus several device-specific commands that [Dan] has added such as

This project combines the SMART Response XE support library by [Larry Bank] with Tiny BASIC Plus, which itself is an update of the Arduino BASIC port by [Michael Field]. The end result is a fun little BASIC handheld that has all the features and capabilities you’d expect, plus several device-specific commands that [Dan] has added such as BATT to check the battery voltage and MSAVE/MLOAD which will save and load BASIC programs to EEPROM.

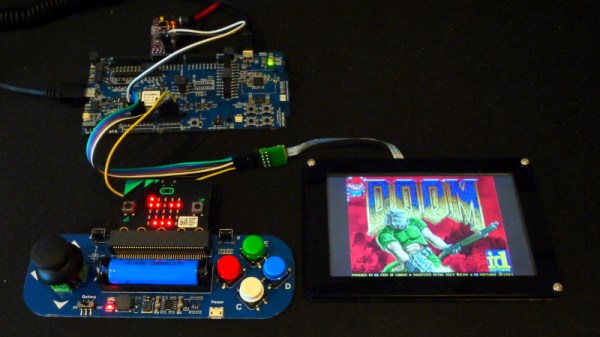

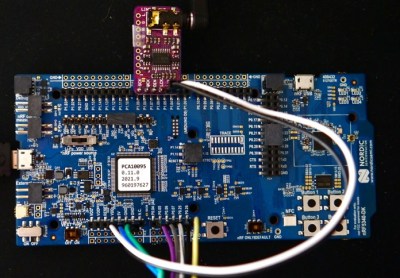

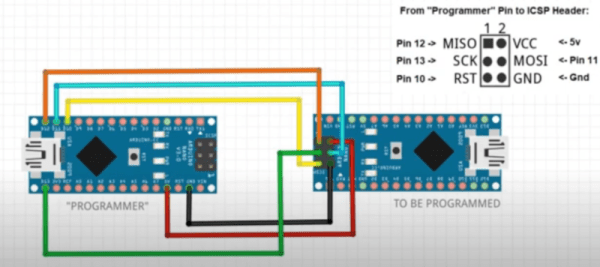

To install the BASIC interpreter to your own SMART Response XE, [Dan] goes over the process of flashing it to the hardware using an AVR ISP MkII and a few pogo pins soldered to a bit of perboard. There are holes under the battery door of the device that exposes the programming pads on the PCB, so you don’t even need to crack open the case. Although if you are willing to crack open the case, you might as well add in a CC1101 transceiver so the handy little device can double as a spectrum analyzer.

Continue reading “SMART Response XE Turned Pocket BASIC Playground”