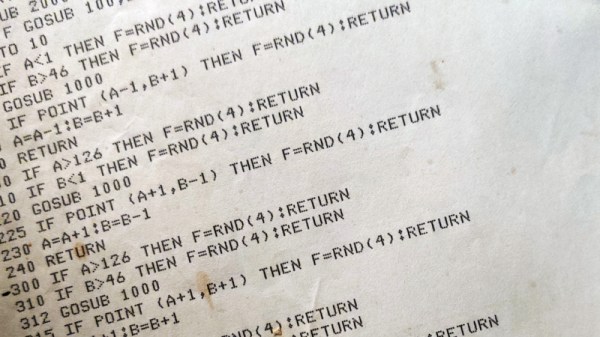

How many of us who have a few decades of adulthood under our belts would like to talk to our 17 year old selves? “Hey kid, it’s all gonna be OK. Also, Duke Nukem Forever does come out eventually, but it’s not going to be pretty!” Being honest, exposure to the hot takes of one’s naive teenage self would almost certainly be as cringeworthy as the time-worn-but-familiar adult would be to the teenager, but there’s one way in which you can in a sense have a conversation with your teenage self. [Mad Ned] had this opportunity, when he discovered a printed BASIC listing for a game he’d written for the TRS-80 back in 1981. Could he make it run again, and what did it tell him about his teenage years?

Grizzled 8-bit veterans will tell you of countless hours spent typing poorly-reproduced listings found in magazines, and the inevitable pain that followed as all those mistypes were ironed out. [Ned] eschewed all that retro experience because this is the 21st century, and we now have much more powerful computers to do our bidding! The reality of incomplete OCR is one we’ll no doubt all be used to, and for 8-bit fans also the debugging that was needed to get the listing to run. Breaker Ball is an odd hybrid of Breakout and Space Invaders, and it’s his analysis of the teenage thinking that led to the game being the way it is that rounds off the piece. Sadly we’re not treated to the entire listing, but there’s a short gameplay video we’ve placed below the break.