To get the perfect mix for your paint, you need a good shake that is as random as possible. [Mark Rhodes] wanted to automate the process of mixing paint, so he built a 3D printed shaker to thoroughly shake small paint bottles. Using only a single motor, it shakes the bottle along three axes of rotation and one axis of translation.

A cylindrical container is attached to a U-shaped bracket on each end, which in turn is attached to a rotating shaft. Only one of these shafts are powered, the other is effectively an idler. When turned on, it rotates the cylinder partially around the pitch and yaw axis, 360 degrees around the roll axis, and reciprocates it back and forth. The design appears to be based on an industrial mixer known as a “Turbula“. Another interesting feature is how it holds the paint bottle in the cylinder. Several bands are stretched along the inside of the cylinder, and by rotating one of the rings at the end, it creates an hourglass-shaped web that can tightly hold the paint bottle.

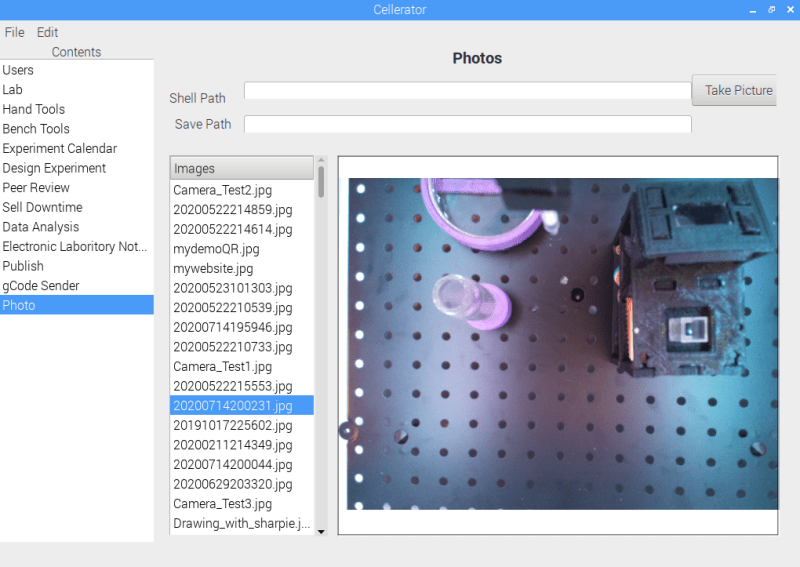

The mechanism is mounted on a 3d printed frame that can be quickly clamped to a table. The Twitter post embedded below is a preview for a video [Mark] is working for his Youtube channel, along with which he will also release the 3D files.

Mixing machines come in all shapes and sizes, and we’ve seen a number of 3D printed versions, including a static mixer and a magnetic stirrer.