Have you been wanting to build your own keyboard, ergonomic or otherwise, but are hesitant to spend all that time and filament on something that may not be a good fit for your hands? Glad as we are that the dactyl is open-source, to get in there and really mess around with it requires intimate knowledge of either OpenSCAD or Clojure.

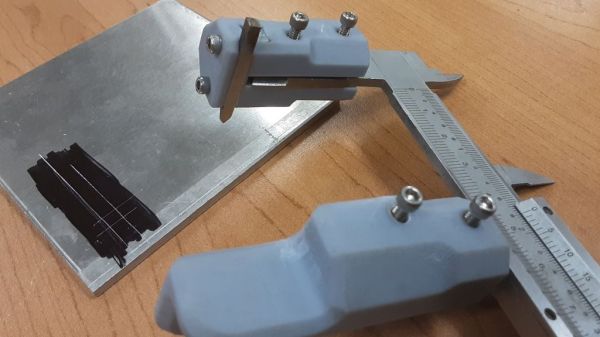

Well, not anymore. [WolfIcefang]’s dactyl chimera is an ergo sandbox, a test bench for column curvature, stagger, and height that should keep you from having to iterate all day and night. It was designed in FreeCAD and has three parts — the rack, the tenting foot, and the arches. The rack acts like a bottom plate and has slots for holding the columns (arches) in place. Underneath that is the tenting foot, which changes the lateral inclination. Thirdly are the arches, the business part where the switches go.

[WolfIcefang] says it’s sturdy but not portable, and for some reason feels the need to apologize for the looks. We think it’s beautiful, but then again are easily captivated by such practicality. It’s not quite a keyboard yet, as [WolfIcefang] has neither wired it up nor burned in any firmware. This is still in the early stages, and [WolfIcefang] wants to open it up to collaborators. Plans for the future include interchangeable thumb clusters and a complete build guide.

Even if you aren’t that fluent in OpenSCAD, you’ll have fun messing around on the keycap modeling playground.