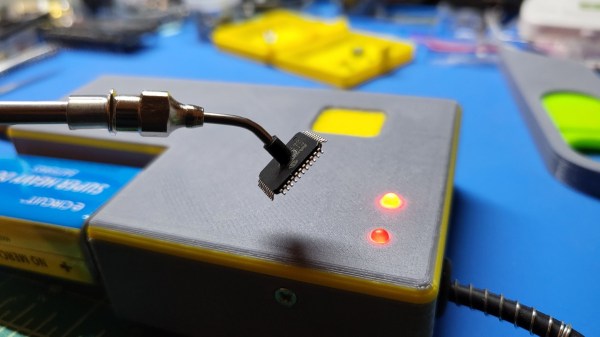

[Dan Julio] owns a pair of Miniware multimeter tweezers, a nifty helper tool for all things SMD exploration. One day, he found them broken – unable to recognize any component between the two probes. He thought it could be a broken connection problem, and decided to take them apart. Presence of some screws on their case fooled him – in the end, it turned out that the case was glued together, and could only be opened destructively. For an entry in the “Reuse, Recycle, Revamp” round of 2022 Hackaday Prize, he tells us how he brought these tweezers back from the dead.

During the disassembly, he broke a custom flexible PCB, which wasn’t reassuring either. However, that was no reason to give up – he reverse-engineered the connections and the charging circuitry, then assembled parts of the broken tweezers together using a small generic protoboard as a base. Indeed, it was likely a broken connection between probes, because the reassembled tweezers worked!

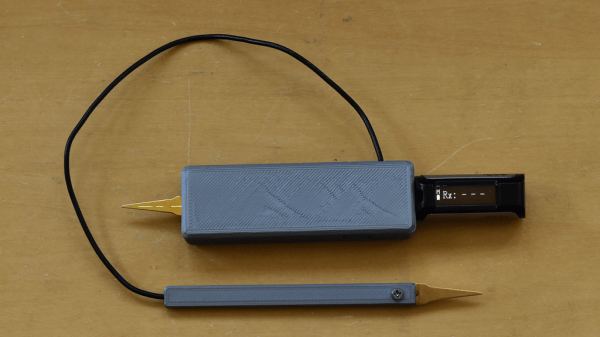

Of course, having exposed PCBs wouldn’t do, and from the very start, assembling these tweezers back together was not an option. Instead, he developed a replacement case in OpenSCAD, bringing the tweezers back to life as his trusty tool – and still leaving repairability on the table. If you’re interested in the details, he goes more into how these tweezers are designed when it comes to charging and connectivity, and we recommend that you give his write-up a read!

We’ve been seeing smart tweezers around for over a decade now, from reviews and hacks of commercially made ones, to DIY chopstick-based and PCB-based ones. If you already own a pair of tweezers you’ve grown attached to, you can neatly retrofit them with a capacitance sensing function!