An interesting trend over the last year or two has been the emergence of modern retrocomputer PCs, recreations of classic PC hardware from back in the day taking advantage of modern parts alongside the venerable processors. These machines are usually very well specified for a PC from the 1980s, and represent a credible way to run your DOS or early Windows software on something close to the original. [CNX Software] has news of a couple of new ones from the same manufacturer in China, one sporting a 386sx and the other claiming it can take either an 8088 or an 8086.

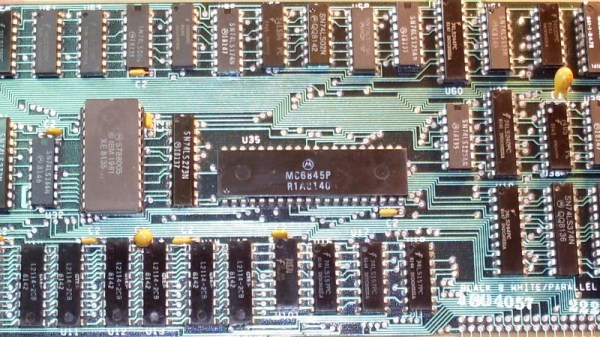

Both machines use the same see-through plastic case, screen, and keyboard, and there are plenty of pictures to examine the motherboard. There are even downloadable design files, which is an interesting development. They come with a removable though proprietary looking VGA card bearing a Tseng Labs ET4000, a CF card interface, a USB port which claims to support disk drives, a sound card, the usual array of ports, and an ISA expansion for which a dock is sold separately. The battery appears to be a LiPo pouch cell of some kind.

If you would like one they can be found through the usual channels for a not-outrageous price compared to similar machines. We can see the attraction, though maybe we’ll stick with an emulator for now. If you’d like to check out alternatives we’ve reported in the past on similar 8088 and 386sx computers.