Reverse engineering a payphone doesn’t sound like a very interesting project, at least in the United States, where payphones were little more than ruggedized versions of residential phones with a coin mechanism attached. Phones in other parts of the world were far more interesting, though, as this look at the mysteries of a payphone from Israel reveals (in Hebrew; English translation here.)

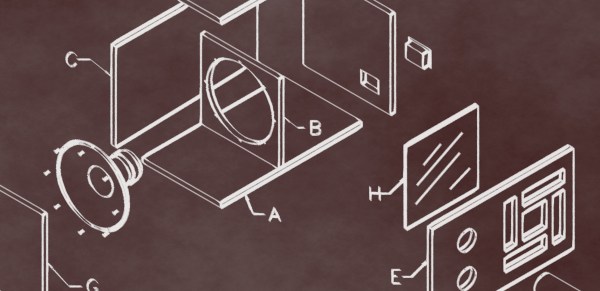

This is a project [Inbar Raz] worked on quite a while ago, but only got around to writing up recently. The payphone in question was sourced from the usual surplus market channels, and appears to have been removed from service by Israeli telecommunications company Bezeq only shortly before he found it. It was in pretty good shape, and was even still locked tight, making some amateur locksmithing the first order of the day. The internals of the phone are surprisingly complex, with a motherboard that looks more like something from a PC. Date codes on the chips and through-hole construction date the device to the early- to mid-1990s.

With physical access gained, [Inbar] turned to the firmware. An Atmel flash chip seemed a good place to look, and indeed he was able to pull code off the chip. That’s where things took a turn thanks to the CPU the code was written for — the CDP1806, a later version of the more popular but still fringe CDP1802. This required [Inbar] to fall down the rabbit hole of writing a new processor definition file for Ghidra so that the firmware could be reverse-engineered. This got him to the point of understanding 1806 assembly well enough that he was able to re-flash the phone to print debugging messages on the built-in 16×2 LCD screen, which allowed him to figure out which routines were being called under various error conditions.

It doesn’t appear that [Inbar] ever completed the reverse engineering project, but as he points out, what does that even mean? He got inside, took a look around, and made the phone do some cool things it couldn’t do before, and in the process made things easier for anyone working with 1806 processors in Ghidra. That’s a pretty complete win in our books.