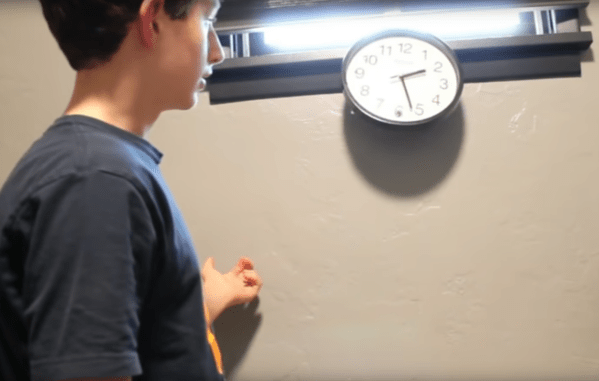

Useless machines are a fun class of devices which typically turn themselves off once they are switched on, hence their name. Even though there’s no real point, they’re fun to build and to operate nonetheless. [Burke] has followed this idea in spirit by putting an old clock he had to use with his take on a useless machine of sorts. But instead of simply powering itself off when turned on, this useless machine dislodges itself from its wall mount and falls to the ground anytime anyone looks at it.

It’s difficult to tell if this clock was originally broken when he started this project, or if many rounds of checking the time have caused the clock to damage itself, but either way this project is an instant classic. Powered by a small battery driving a Raspberry Pi, the single-board computer runs OpenCV and is programmed to recognize any face pointed in its general direction. When it does, it activates a small servo which knocks it off of its wall, rendering it unarguably useless.

[Burke] doesn’t really know why he had this idea, but it’s goofy and fun. The duct tape that holds everything together is the ultimate finishing touch as well, and we can’t really justify spending too much on fit and finish for a project that tosses itself around one’s room. On the other hand, if you’re looking for a more refined useless machine, we have seen some that have an impressive level of intricacy.

Thanks to [alchemyx] for the tip!