We like to think that we can do almost anything. Give me a broken piece of consumer electronics, and I’ll open it up and kick the capacitors. Give me an embedded Linux machine, and I’ll poke around for a serial port and see if it’s running uboot. But my confidence suddenly pales when you hand me a smartphone.

Now that’s not to say that I’ve never replaced a broken screen or a camera module with OEM parts. The modern smartphone is actually a miracle of modularity, with most sub-assemblies being swappable, at least in principle, and depending on your taste for applying heat to loosen up whatever glue holds the damn things together.

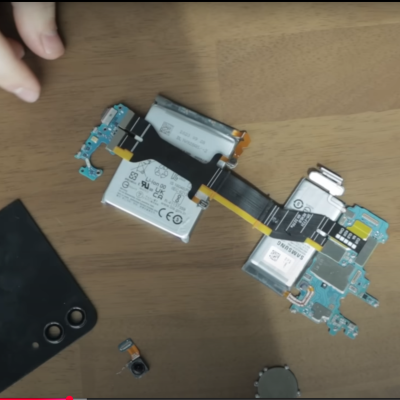

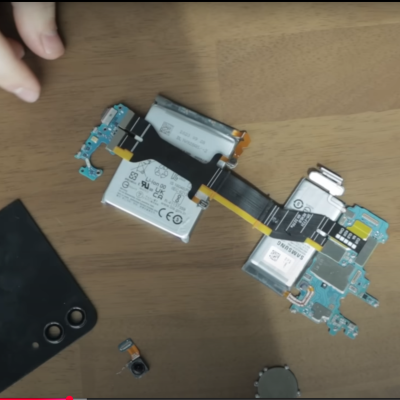

But actually doing hardware hacking on smartphones is still outside of my comfort zone, and that’s a shame. So I was pretty pleased to see [Marcin Plaza] attempt gutting a smartphone, repackaging it into a new form factor, and even adding a new keyboard to it. The best moment in that video for me comes around eight minutes in, when he has completely disassembled all of the modules and is laying them out on his desk to see how little he needs to make the thing work. And the answer is batteries, motherboard, USB-C, power button, and a screen. That starts to seem like a computer build, and that’s familiar turf.

But actually doing hardware hacking on smartphones is still outside of my comfort zone, and that’s a shame. So I was pretty pleased to see [Marcin Plaza] attempt gutting a smartphone, repackaging it into a new form factor, and even adding a new keyboard to it. The best moment in that video for me comes around eight minutes in, when he has completely disassembled all of the modules and is laying them out on his desk to see how little he needs to make the thing work. And the answer is batteries, motherboard, USB-C, power button, and a screen. That starts to seem like a computer build, and that’s familiar turf.

That reminded me of [Scotty Allen]’s forays into cell-phone hackery that culminated in his building one completely from parts, and telling us all about it at Supercon ages ago. He told me that the turning point for him was realizing that if you have access to the tools to put it together and can get some of the impossibly small parts manufactured and/or assembled for you, that it’s just like putting a computer together.

So now I’ve seen two examples. [Scotty] put his together from parts, and [Marcin] actually got a new daughterboard made that interfaces with the USB to add a keyboard. Hardware hacking on a cellphone doesn’t sound entirely impossible. You’d probably want a cheap old used one, but the barrier to entry there isn’t that bad. You’ll probably have to buy some obscure connectors – they are tiny inside smartphones – and get some breakout boards made. But maybe it’s possible?

Anyone have more encouragement?