Here at Hackaday, we pride ourselves on bringing you the freshest of hacks, preferably as soon as we find out about them. Thanks to the sheer volume of cool hacks out there, though, we do miss one occasionally, like this e-waste horizontal CNC mill that we just found out about.

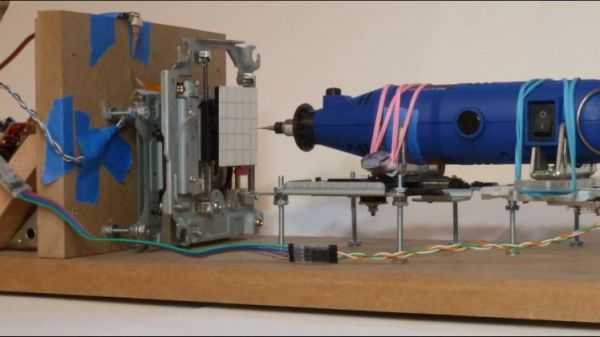

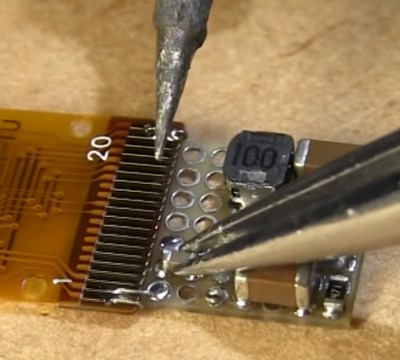

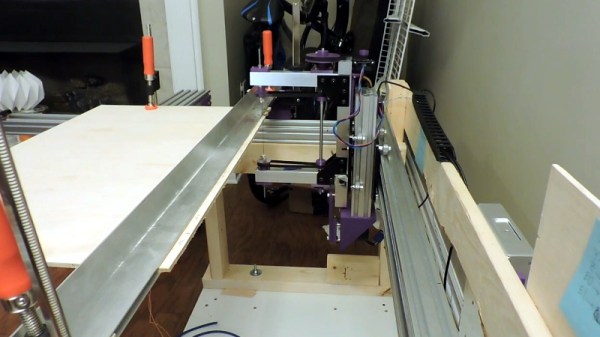

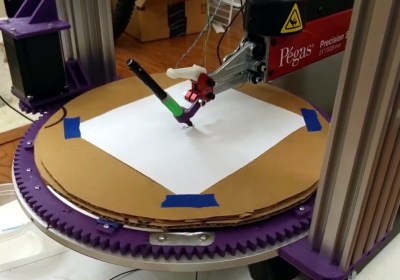

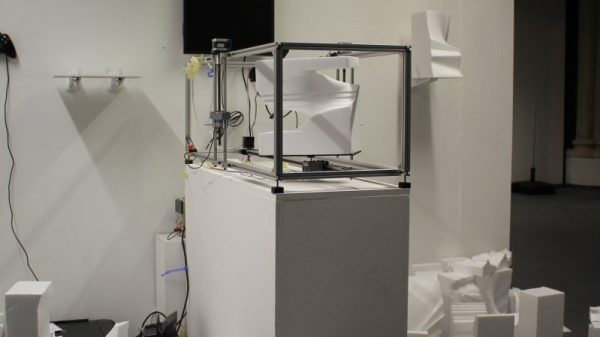

Aptly called the “CDCNC” thanks to its reliance on cast-off CD drive mechanisms for its running gear, [Paul McClay]’s creation is a great case study on what you can do without buying almost any new parts. It’s also an object lesson in not getting caught in standard design paradigms. Where most CNC mills mount the spindle vertically, [Paul] tilted the whole thing 90 degrees so the spindle lies on its side. Moving it back and forth on a pair of CD drive mechanisms is far easier than fighting gravity for control, and as a bonus the X- and Y-axes have minimal loading too. The video below shows the mill in action, and it’s easy to see how the horizontal arrangement really helps make this junk bin build into something special.

We think [Paul] did a great job of thinking around the problem with this build, and we’re glad he took the time to tip us off. Apparently it was the upcoming CNC on the Desktop Hack Chat that moved him to let us know about this build. Here’s hoping he drops by for the chat and shares his experience with us.

Continue reading “Mini CNC Mill Goes Horizontal To Reuse CD Drives”