Join us on Wednesday, March 4 at noon Pacific for the On-Demand Manufacturing Hack Chat with Dan Emery!

The classical recipe for starting a manufacturing enterprise is pretty straightforward: get an idea, attract investors, hire works, buy machines, put it all in a factory, and profit. Things have been this way since the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, and it’s a recipe that has largely given us the world we have today, for better and for worse.

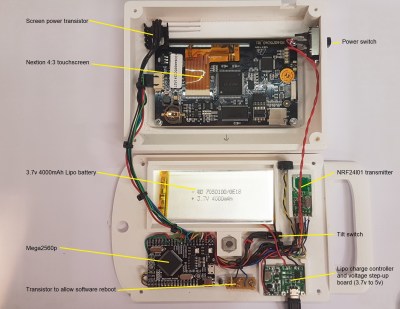

One of the downsides of this model is the need for initial capital to buy the machines and build the factory. Not every idea will attract the kind of money needed to get off the ground, which means that a lot of good ideas never see the light of day. Luckily, though, we live in an age where manufacturing is no longer a monolithic process. You can literally design a product and have it tested, manufactured, and sold without ever taking one shipment of raw materials or buying a single machine other than the computer that makes this magic possible.

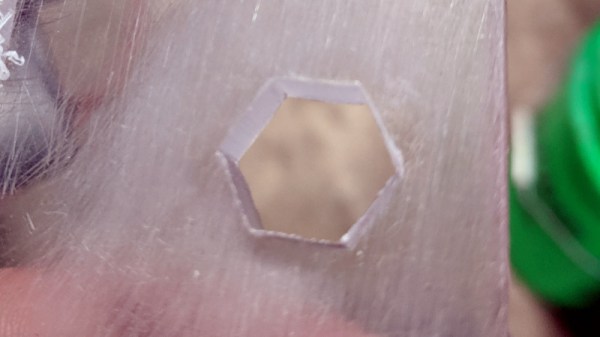

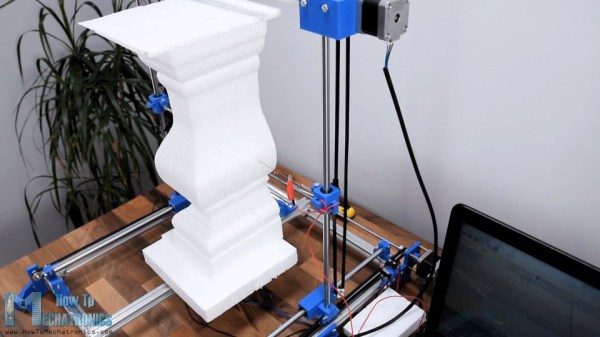

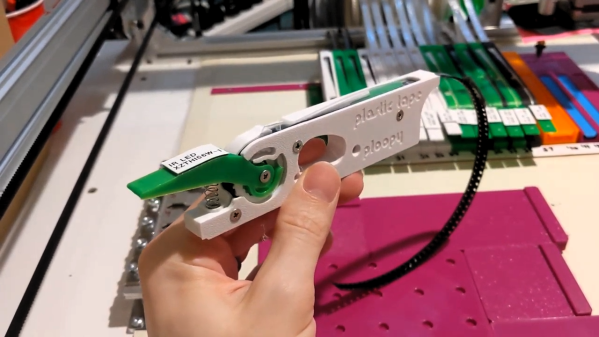

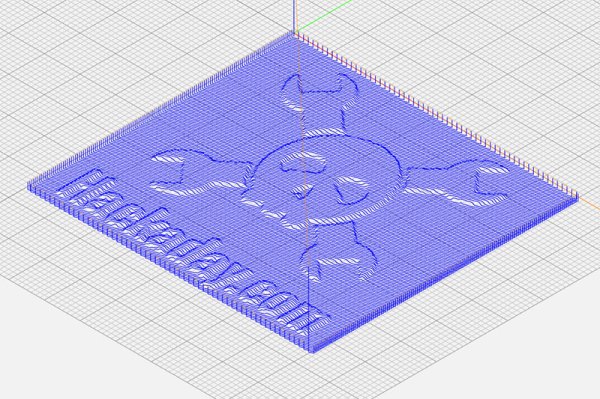

As co-founder of Ponoko, Dan Emery is in the thick of this manufacturing revolution. His company capitalizes on the need for laser cutting, whether it be for parts used in rapid prototyping or complete production runs of cut and engraved pieces. Their service is part of a wider ecosystem that covers almost every additive and subtractive manufacturing process, including 3D-printing, CNC machining, PCB manufacturing, and even final assembly and testing, providing new entrepreneur access to tools and processes that would have once required buckets of cash to acquire and put under one roof.

Join us as we sit down with Derek and discuss the current state of on-demand manufacturing and what the future holds for it. We’ll talk about Ponoko’s specific place in this ecosystem, and what role outsourced laser cutting could play in getting your widget to market. We’ll also take a look at how Ponoko got started and how it got where it is today, as well as anything else that comes up.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, March 4 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, March 4 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.