If you are a follower of retrocomputing, perhaps you caught the interactive Black Mirror episode Bandersnatch when it came out on Netflix. Its portrayal of a young British bedroom coder finding his way into the home computer games industry of the early 1980s was of course fictional and dramatised, but for those interested in a real-life parallel without the protagonist succumbing to an obsession with supernatural book there’s a recent epic Twitter thread charting an industry veteran’s path into the business.

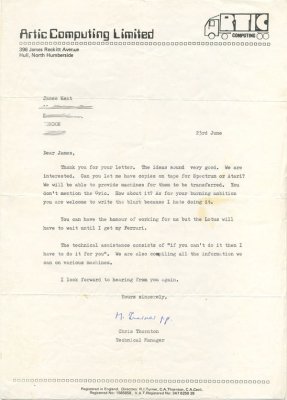

[Shahid Kamal Ahmad] now has an impressive portfolio spanning his his nearly four decades at the forefront of gaming, but his story starts in 1982 as a diabetic British Pakistani teenager from a not-privileged background in London writing in BASIC on his Atari 400. His BASIC games are good, but not good enough to gain acceptance from a publisher, so he sells his prized BMX bicycle to buy books on Atari 6502 assembler, a coffee percolator, and for curiosity’s sake, [Rodnay Zaks’] Programming the Z80. An obsessive three-month learning of 6502 programming and the Atari’s architecture ensues, and his game Storm in a Teacup sells to Artic Software. He’s a professional game developer.

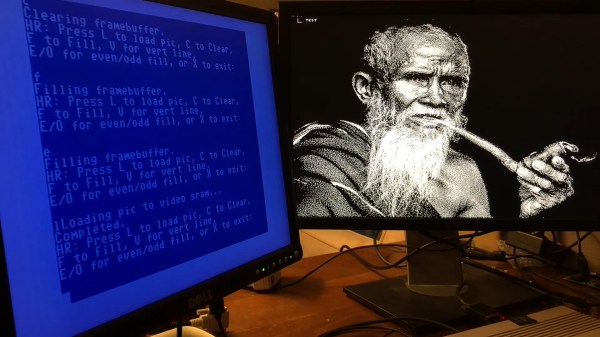

We follow him through a couple more projects until he arrives at Software Projects in Liverpool to try to sell his game Faces of Haarne, which he secures publishing for but also lands the opportunity of a lifetime. Jet Set Willy is the smash hit of the year on the ZX Spectrum, and they urgently need a Commodore 64 port. Can he do it in four weeks, with a bonus if he manages three? The subsequent descent into high-pressure assembly coding and learning the quirks between two completely different 8-bit architectures is an epic in itself, but he manages it in just a shade over the three weeks and they pay him the bonus anyway. His career in the computer game industry is cemented.

Through this tale the reminders of 1980s Britain are everywhere, far from bring a retro paradise it was a place hollowed out by industrial decline, with very little for those at the bottom of society to be optimistic about. His descriptions of casual racism are hard-hitting, but the group of computer-addicted friends at school is probably something that all teenagers of the era whose interests lay in that direction can relate to. The real hero of the story is probably his mother, who somehow found the resources for that Atari 400 and who provided him with much-needed support and encouragement.

This thread captures a unique and never-to-be repeated era in which a teenager could master an emerging technology and make a living in it without an expensive education. Like Bil Herd’s description of his career at Commodore in the same period, it’s well worth a read.