This may come as a shock, but some of those hot screaming deals on China-sourced gadgets and goodies are not all they appear. After you plunk down your pittance and wait a few weeks for the package to arrive, you just might find that you didn’t get exactly what you thought you ordered. Or worse, you may get a product with unwanted bugs features, like some green lasers that also emit strongly in the infrared wavelengths.

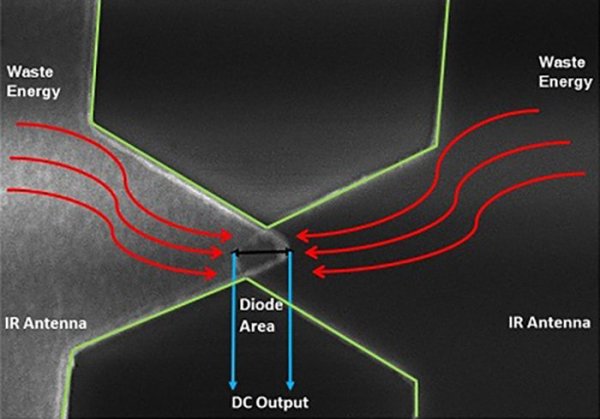

Sure, getting a free death ray in addition to your green laser sounds like a bargain, but as [Brainiac75] points out, it actually represents a dangerous situation. He knows whereof he speaks, having done a thorough exploration of a wide range of cheap (and not so cheap) lasers in the video below. He explains that the paradox of an ostensibly monochromatic source emitting two distinct wavelengths comes from the IR laser at the heart of the diode-pumped solid state (DPSS) laser inside the pointer. The process is only about 48% efficient, meaning that IR leaks out along with the green light. The better quality DPSS laser pointers include a quality IR filter to remove it; cheaper ones often fail to include this essential safety feature. What wavelengths you’re working with are critical to protecting your eyes; indeed, the first viewer comment in the video is from someone who seared his retina with a cheap green laser while wearing goggles only meant to block the higher frequency light.

It’s a sobering lesson, but an apt one given the ubiquity of green lasers these days. Be safe out there; educate yourself on how lasers work and take a look at our guide to laser safety. Continue reading “Science Shows Green Lasers Might Be More Than You Bargained For”