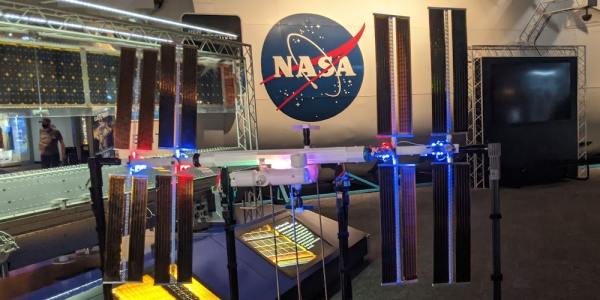

It’s not an overstatement to say that the International Space Station (ISS for short) is an amazing feat of engineering, especially considering that it has been going for over two decades. The international collaboration isn’t just for the governments, either, as many images, collected data and even some telemetry have been made available to the public. This telemetry inspired [Bryan Murphy] and his team to create the ISS MIMIC, a 1:100 scale model of the ISS that reflects its space counterpart.

The model, covered by [3D Printing Nerd] after the break, receives telemetry from the real ISS and actually reflects the orientation of the solar panels accordingly! It also uses this entirely public information to show other things like battery charge level, power production, position above the earth and more on a display. An extra detail we appreciated is the LEDs near the solar panels, which are red, blue or white to indicate using battery, charging battery and full battery respectively. The ISS orbits the earth once every 90 minutes, which can be seen by the LEDs changing color as the ISS enters the shadow of the earth, or exits it.

What could you do to make this better you might ask? Make the it open-source of course! The ISS MIMIC is fully open-source and uses common tools like 3D printing with PLA, Raspberry Pis and Arduinos to make it as accessible as possible for education (and hackers). Naturally, the goal of this project is to educate, which is why it’s open-source and aims to teach programming, electronics, mechatronics and problem solving.

Video after the break.

Continue reading “This Model Mimics The International Space Station”