Back in high school, all the serious gearheads used to brag about two things: their drag strip tickets, and their dynamometer reports. The former showed how fast their muscle car could cover a quarter-mile, while the latter was documentation on how much power their carefully crafted machine could deliver. What can I say; gas was cheap and we didn’t have the Internet to distract us.

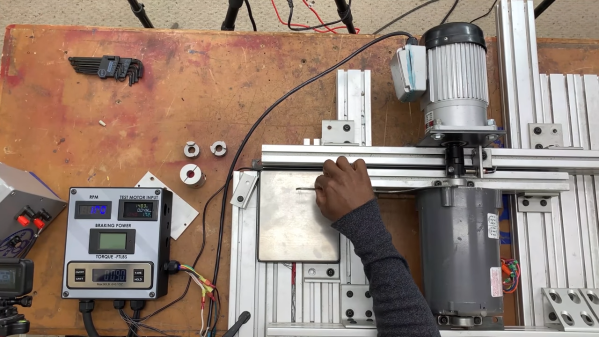

Bragging rights are not exactly what [Jeremy Fielding] has in mind for his DIY dynamometer, nor is getting the particulars on a big Detroit V8 engine. Rather, he wants to characterize small- to medium-sized electric motors, with an eye toward repurposing them for different projects. To do this, he built a simple jig to measure the two parameters needed to calculate the power output of a motor: speed and torque. A magnetic tachometer does the job of measuring the motor’s speed, but torque proved a bit more challenging. The motor under test is coupled to a separate electric braking motor, which spins free when it’s not powered. A lever arm of known length connects to the braking motor on one end while bearing on a digital scale on the other. With the motor under test spun up, the braking motor is gradually powered, which rotates its housing and produces a force on the scale through the lever arm. A little math is all it takes for the mystery motor to reveal its secrets.

[Jeremy]’s videos are always instructional, and the joy he obviously feels at discovery is infectious, so we’re surprised to see that we haven’t featured any of his stuff before. We’ve seen our share of dynos before, though, from the tiny to the computerized to the kind that sometimes blows up.

Continue reading “This DIY Dynamometer Shows Just What A Motor Can Do”

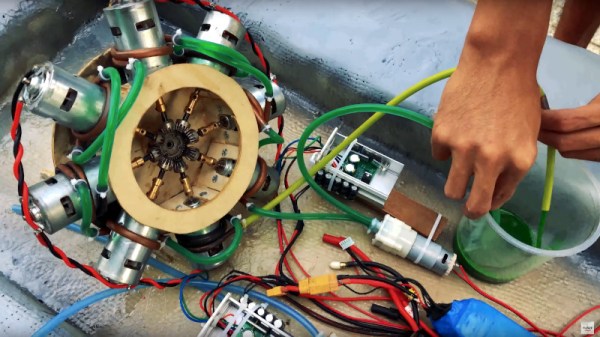

[madcowswe] starts by pointing out that the entire premise of ODrive (an open-source brushless motor driver board) is to make use of inexpensive brushless motors in industrial-type applications. This usually means using hobby electric aircraft motors, but robotic applications sometimes need more torque than those motors can provide. Adding a gearbox is one option, but there is another: so-called “hoverboard” motors are common and

[madcowswe] starts by pointing out that the entire premise of ODrive (an open-source brushless motor driver board) is to make use of inexpensive brushless motors in industrial-type applications. This usually means using hobby electric aircraft motors, but robotic applications sometimes need more torque than those motors can provide. Adding a gearbox is one option, but there is another: so-called “hoverboard” motors are common and