We are smack-dab in the middle of our Energy Harvesting Challenge, and [wasimashu] might have this one in the palm of his hand. Imagine a compact flashlight that doesn’t need batteries or bulbs. You’d buy a 10-pack and stash them everywhere, right? If there’s nothing that will leak or break or expire in your lifetime, why not have a bunch of them around?

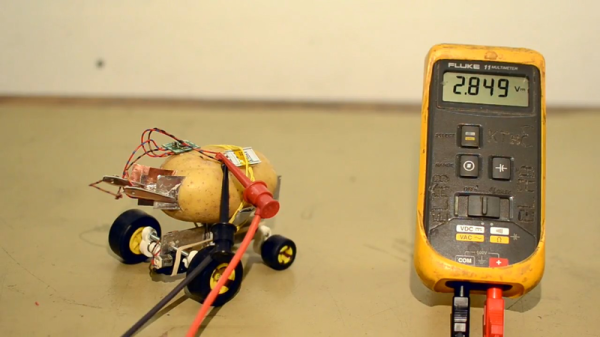

Infinity uses nothing but body heat to power a single white LED. It only needs a five-degree temperature difference between the air and your hand to work, so it should be good in pretty much any environment. While it certainly won’t be the brightest light in your collection, it’s a whole lot better than darkness. Someday, it might be the only light around that works.

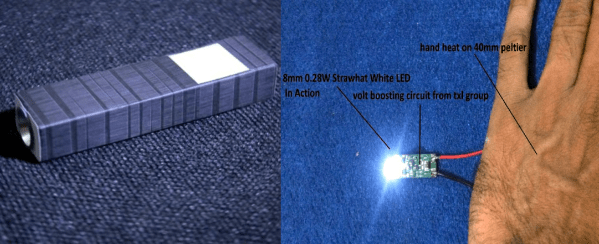

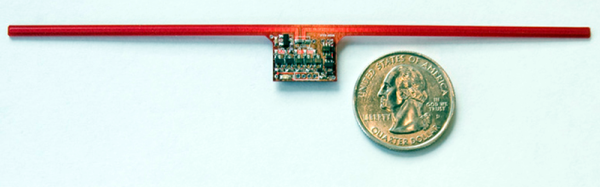

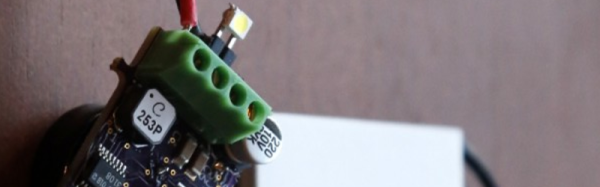

As you might expect, there’s a Peltier unit involved. Two of them, actually. Both are embedded flush on opposite sides of the hollow aluminum flashlight body, which acts as a heat sink and allows air to pass through. After trying to boost the output voltage with a homemade feedback oscillator and hand-wound transformers, [wasimashu] settled on a unipolar boost converter to reach the 5V needed to power the LED.

[wasimashu] has made it his personal mission to help humanity through science. We’d say that Infinity puts him well on the way, and can’t wait to see what he does next.