Though threading is a old concept in computer science, and fabric computing has been a term for about thirty years, the terminology has so far been more metaphorical than strictly descriptive. [Cedric Honnet]’s FiberCircuits project, on the other hand, takes a much more literal to weaving technology “into the fabric of everyday life,” to borrow the phrase from [Mark Weiser]’s vision of computing which inspired this project. [Cedric] realized that some microcontrollers are small enough to fit into fibers no thicker than a strand of yarn, and used them to design these open-source threads of electronics (open-access paper).

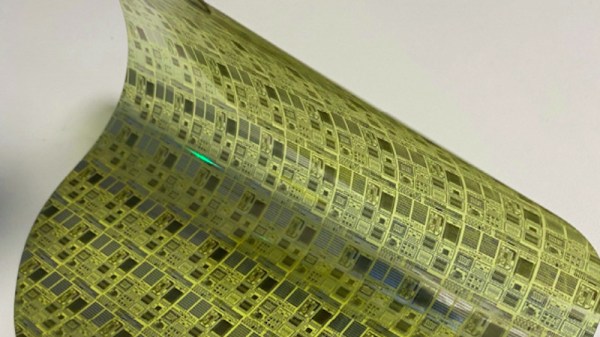

The physical design of the FiberCircuits was inspired by LED filaments: a flexible PCB wrapped in a protective silicone coating, optionally with a protective layer of braiding surrounding it. There are two kinds of fiber: the main fiber and display fibers. The main fiber (1.5 mm wide) holds an STM32 microcontroller, a magnetometer, an accelerometer, and a GPIO pin to interface with external sensors or other fibers. The display fibers are thinner at only one millimeter, and hold an array of addressable LEDs. In testing, the fibers could withstand six Newtons of force and be bent ten thousand times without damage; fibers protected by braiding even survived 40 cycles in a washing machine without any damage. [Cedrik] notes that finding a PCB manufacturer that will make the thin traces required for this circuit board is a bit difficult, but if you’d like to give it a try, the design files are on GitHub.

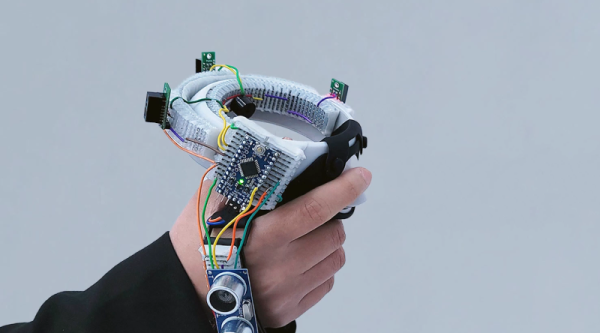

[Cedrik] also showed off a few interesting applications of the thread, including a cyclist’s beanie with automatic integrated turn signals, a woven fitness tracker, and a glove that senses the wearer’s hand position; we’re sure the community can find many more uses. The fibers could be embroidered onto clothing, or embedded into woven or knitted fabrics. On the programming side, [Cedrik] ported support for this specific STM32 core to the Arduino ecosystem, and it’s now maintained upstream by the STM32duino project, which should make integration (metaphorically) seamless.

One area for future improvement is in power, which is currently supplied by small lithium batteries; it would be interesting to see an integration of this with power over skin. This might be a bit more robust, but it isn’t first knitted piece of electronics we’ve seen. Of course, rather than making wearables more unobtrusive, you can go in the opposite direction. Continue reading “Weaving Circuits From Electronic Threads”