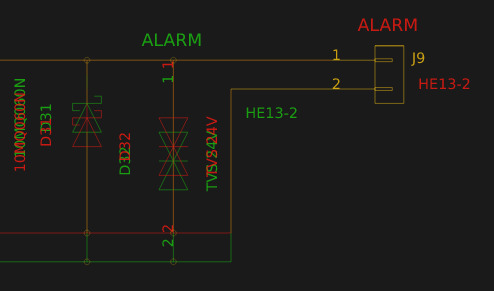

For most developers “distributed version control” probably means git. But by itself git doesn’t work very well with binary files such as images, zip files and the like because git doesn’t know how to make sense of the structure of an arbitrary blobs of bytes. So when trying to figure out how to track changes in design files created by most EDA tools git doesn’t get the nod and designers can be trapped in SVN hell. It turns out though KiCAD’s design files may not have obvious extensions like .txt, they are fundamentally text files (you might know that if you’ve ever tried to work around some of KiCAD’s limitations). And with a few tweaks from [jean-noël]’s guide you’ll be diffing and merging your .pro’s and .sch’s with aplomb.

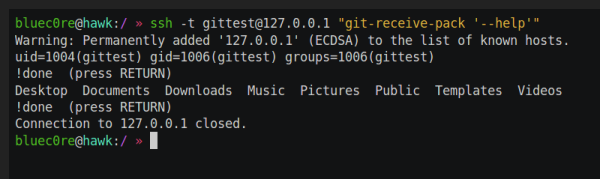

There are a couple sections to the document (which is really meant as an on boarding to another tool, which we’ve gotten to in another post). The first chunk describes which files should be tracked by the repo and which the .gitignore can be configured to avoid. If that didn’t make any sense it’s worth the time learning how to keep a clean repo with the magic .gitignore file, which git will look for to see if there are any file types or paths it should avoid staging.

The second section describes how you can use two nifty git features, cleaning and smudging, to dynamically modify files as they are checked in and out of the repo. [jean-noël]’s observation is that certain files get touched by KiCAD even if there are no user facing changes, which can clutter patch sets with irrelevant changes. His suggested filters prevent this by stripping those changes out as files get checked in. Pretty slick.