Ordinarily, when we need gears, we pop open a McMaster catalog or head to the KHK website. Some of the more adventurous may even laser cut or 3D print them. But what about machining them yourself?

[Uri Tuchman] set out to do just that. Of course, cutting your own gears isn’t any fun if you didn’t also build the machine that does the cutting, right? And let’s be honest, what’s the point of making the machine in the first place if it doesn’t double as a work of art?

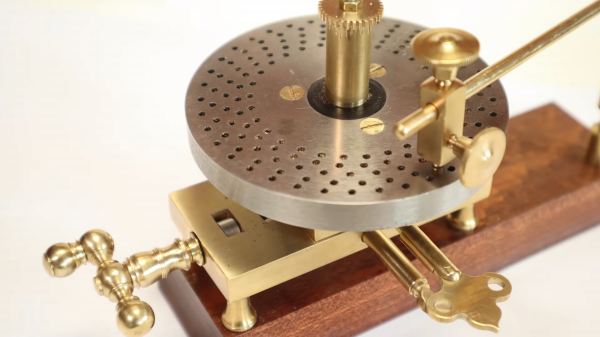

[Uri’s] machine, made from brass and wood, is simple in its premise. It is placed adjacent to a gear cutter, a spinning tool that cuts the correct involute profile that constitutes a gear tooth. The gear-to-be is mounted in the center, atop a hole-filled plate called the dividing plate. The dividing plate can be rotated about its center and translated along linear stages, and a pin drops into each hole on the plate as it moves to index the location of each gear tooth and lock the machine for cutting.

The most impressive part [Uri’s] machine is that it was made almost entirely with hand tools. The most advanced piece of equipment he used in the build is a lathe, and even for those operations he hand-held the cutting tool. The result is an elegant mechanism as beautiful as it is functional — one that would look at home on a workbench in the late 19th century.

[Thanks BaldPower]

Continue reading “Homemade Gear Cutting Indexer Blends Art With Engineering”

[Tony Goacher] took this idea a few steps further when he created the

[Tony Goacher] took this idea a few steps further when he created the

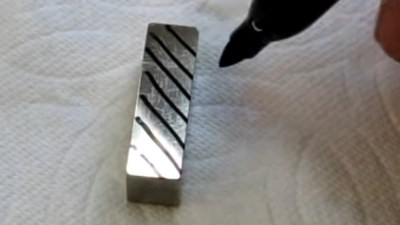

[Tom] from [oxtoolco] got his hands on a tool that measures in 1/10,000,000th (that’s one ten-millionth) increments and was wondering what kind of shenanigans you can do with this Lamborghini of dial indicators. It’s one thing to say you’re going to measure ink, but coming up with the method is the leap. In this case it’s a gauge block — a piece of precision ground metal with precise dimensions and perfectly perpendicular faces. By zeroing the indicator on the block, then adding lines from the Sharpie and measuring again, you can deduce the thickness of the ink markings.

[Tom] from [oxtoolco] got his hands on a tool that measures in 1/10,000,000th (that’s one ten-millionth) increments and was wondering what kind of shenanigans you can do with this Lamborghini of dial indicators. It’s one thing to say you’re going to measure ink, but coming up with the method is the leap. In this case it’s a gauge block — a piece of precision ground metal with precise dimensions and perfectly perpendicular faces. By zeroing the indicator on the block, then adding lines from the Sharpie and measuring again, you can deduce the thickness of the ink markings.