The Kinect is a depth-sensing camera peripheral originally designed as a accessory for the Xbox gaming console, and it quickly found its way into hobbyist and research projects. After a second version, Microsoft abandoned the idea of using it as a motion sensor for gaming and it was discontinued. The technology did however end up evolving as a sensor into what eventually became the Azure Kinect DK (spelling out ‘developer kit’ presumably made the name too long.) Sadly, it also has now been discontinued.

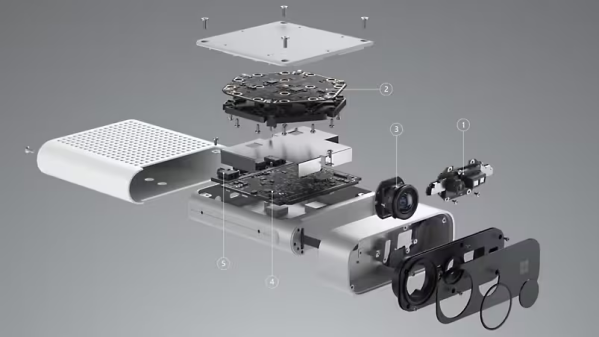

The original Kinect was a pretty neat piece of hardware for the price, and a few years ago we noted that the newest version was considerably smaller and more capable. It had a depth sensor with selectable field of view for different applications, a high-resolution RGB video camera that integrated with the depth stream, integrated IMU and microphone array, and it worked to leverage machine learning for better processing and easy integration with Azure. It even provided a simple way to sync multiple units together for unified processing of a scene.

The original Kinect was a pretty neat piece of hardware for the price, and a few years ago we noted that the newest version was considerably smaller and more capable. It had a depth sensor with selectable field of view for different applications, a high-resolution RGB video camera that integrated with the depth stream, integrated IMU and microphone array, and it worked to leverage machine learning for better processing and easy integration with Azure. It even provided a simple way to sync multiple units together for unified processing of a scene.

In many ways the Kinect gave us all a glimpse of the future because at the time, a depth-sensing camera with a synchronized video stream was just not a normal thing to get one’s hands on. It was also one of the first consumer hardware items to contain a microphone array, which allowed it to better record voices, localize them, and isolate them from other noise sources in a room. It led to many, many projects and we hope there are still more to come, because Microsoft might not be making them anymore, but they are licensing out the technology to companies who want to build similar devices.