For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Martin] is building an Open Source Multimeter that can measure voltage, current, and power. It’s an amazing build, and you too can build one yourself.

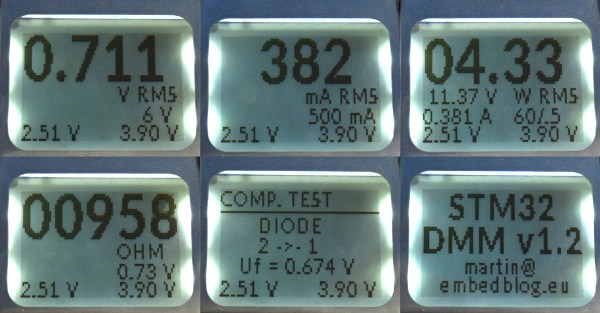

The features for this multimeter consist of voltage mode with a range of +/-6V and +/-60V. There’s a current mode, basically the same as voltage, with a range of +/-60 mA and +/-500mA. Unlike our bright yellow Fluke, there’s also a power mode that measures voltage and current at the same time, with all four combinations of ranges available. There’s a continuity test that sounds a buzzer when the resistance is below 50 Ω, and a component test mode that measures resistors, caps, and diodes. There’s a fully isolated USB interface capable of receiving commands and transmitting data, a real-time clock, and in the future there might be frequency measurement.

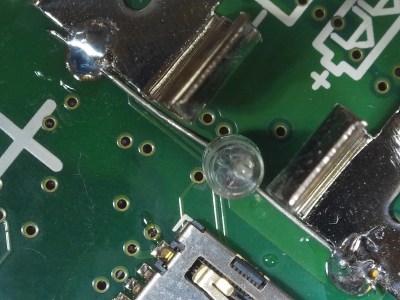

This build is based on the STM32F103 microcontroller, uses an old Nokia phone screen, and unlike so many other multimeters, this thing is small. It’s very small. More than small enough to fit in your pocket and forget about it, unlike nearly every other multimeter available. There’s one thing about multimeters, and it’s that the best multimeter is the one that you have in your hands when you need it, and this one certainly fits the bill.

The entire project is being written up on hackaday.io, there’s a GitHub repo for all the hardware and software, and there’s also a video demo covering all the features (available below). This is a stand-out project, and something we desperately want to get our hands on.

Continue reading “Finally, An Open Source Multimeter” →

Are all cheap multimeter leads similarly useless? Not necessarily. [nop head] also purchased the set pictured here. It has no attachments, but was a much better design and had a resistance of only 64 milliohms. Not great, but certainly serviceable and clearly a much better value than the other set.

Are all cheap multimeter leads similarly useless? Not necessarily. [nop head] also purchased the set pictured here. It has no attachments, but was a much better design and had a resistance of only 64 milliohms. Not great, but certainly serviceable and clearly a much better value than the other set.