First there was [Geohot]’s lofty goal to build a hacker’s version of the self-driving car. Then came comma.ai and a whole bunch of venture capital. After that, a letter from the Feds and a hasty retreat from the business end of things. The latest development? comma.ai’s openpilot project shows up on GitHub!

If you’ve got either an Acura ILX or Honda Civic 2016 Touring addition, you can start to play around with this technology on your own. Is this a good idea? Are you willing to buy some time on a closed track?

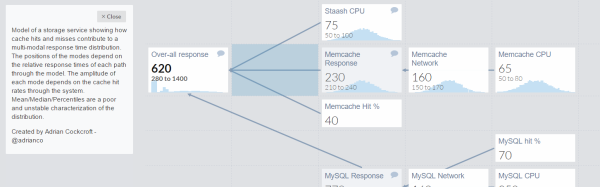

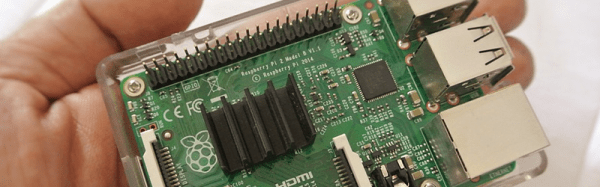

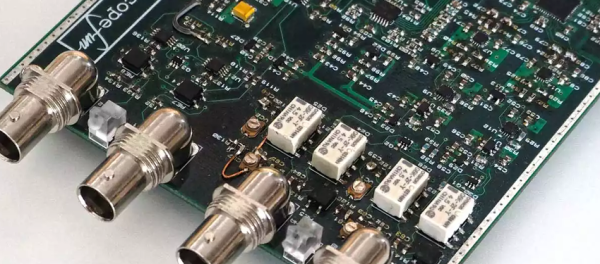

A quick browse through the code gives some clues as to what’s going on here. The board files show just how easy it is to interface with these cars’ driving controls: there’s a bunch of CAN commands and that’s it. There’s some unintentional black comedy, like a (software) crash-handler routine named crash.py.

What’s shocking is that there’s nothing shocking going on. It’s all pretty much straightforward Python with sprinklings of C. Honestly, it looks like something you could get into and start hacking away at pretty quickly. Anyone want to send us an Acura ILX for testing purposes? No promises you’ll get it back in one piece.

If you missed it, read up on our coverage of the rapid rise and faster retreat of comma.ai. But we don’t think the game is over yet: comma.ai is still hiring. Are open source self-driving cars in our future? That would be fantastic!

Via Endagadget. Thanks for the tip, [FaultyWarrior]!