Although it can be hard to imagine in today’s semiconductor-powered, digital world, there was electrical technology around before the widespread adoption of the transistor in the latter half of the 1900s that could do more than provide lighting. People figured out clever ways to send information around analog systems, whether that was a telegraph or a telephone. These systems are almost completely obsolete these days thanks to digital technology, leaving a large number of rotary phones and other communications systems relegated to the dustbin of history. [Attoparsec] brought a few of these old machines back to life anyway, setting up a local intercom system with technology faithful to this pre-digital era.

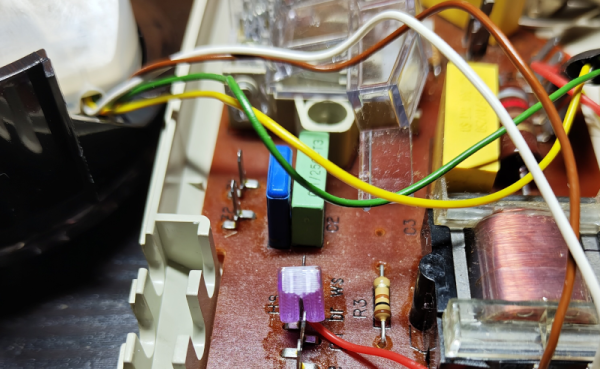

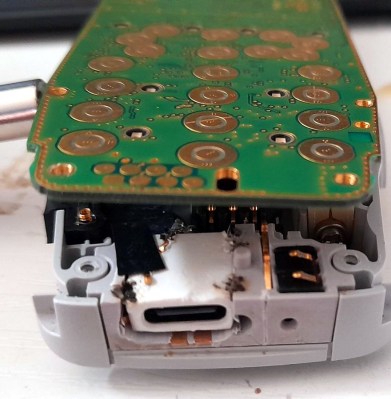

These phones date well before the rotary phone that some of us may be familiar with, to a time where landline phones had batteries installed in them to provide current to the analog voice circuit. A transformer isolated the DC out of the line and amplified the voice signal. A generator was included in parallel which, when operated by hand, could ring the other phones on the line. The challenge to this build was keeping everything period-appropriate, with a few compromises made for the batteries which are D-cell batteries with a recreation case. [Attoparsec] even found cloth wiring meant for guitars to keep the insides looking like they’re still 100 years old. Beyond that, a few plastic parts needed to be fabricated to make sure the circuit was working properly, but for a relatively simple machine the repairs were relatively straightforward.

The other key to getting an intercom set up in a house is exterior to the phones themselves. There needs to be some sort of wiring connecting the phones, and [Attoparsec] had a number of existing phone wiring options already available in his house. He only needed to run a few extra wires to get the phones located in his preferred spots. After everything is hooked up, the phones work just as they would have when they were new, although their actual utility is limited by the availability of things like smartphones. But, if you have enough of these antiques, you can always build your own analog phone network from the ground up to support them all.

Continue reading “A Working Intercom From Antique Telephones”