It’s a truth universally acknowledged that sometimes a little music can add much to a nice afternoon picnic. It’s also well-known that meat cooked over hot coals should be turned regularly to allow for even cooking. This barbecue grille project from [Handy Geng] delivers on both counts.

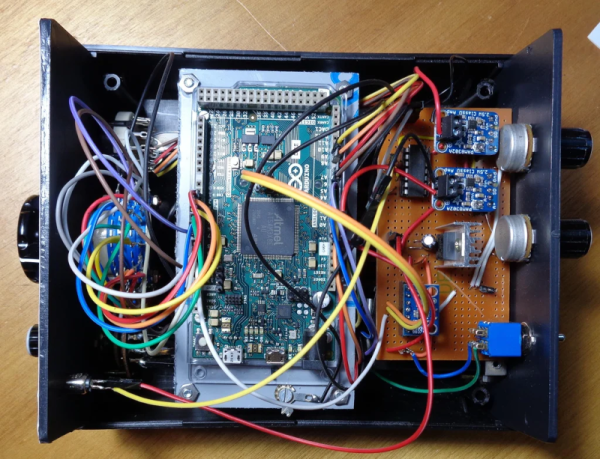

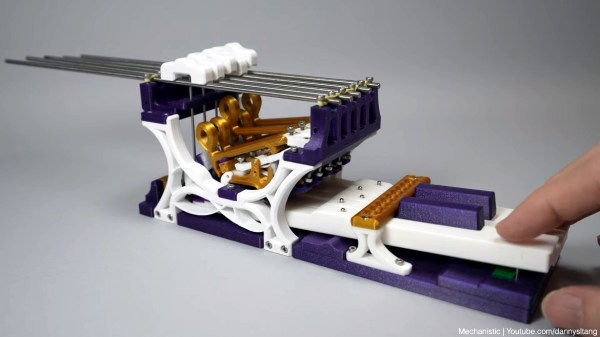

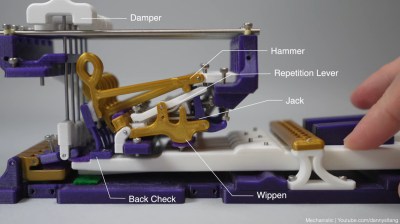

The project uses a full 88 motors, activated by pressing keys on an electronic piano. The technique used is simple; rather than interface with the keyboard electronically or over MIDI, instead, a microswitch is installed under each individual key.

Thus, when the piano keys are pressed, the corresponding motors are switched on. Each motor turns a skewer loaded with meat, sitting above a box of hot coals. Thus, playing the piano turns the meat, allowing it to be cooked on all sides without burning.

As a further bonus, the entire piano barbecue grille is also motorized, allowing [Handy Geng] to do laps around his workshop while playing the piano and cooking up lunch. It’s a great way to cook up some grilled kebabs while simultaneously entertaining one’s guests.

We’ve seen some other fun grill hacks too – even robotic ones! Video after the break.

Continue reading “Finally, A Piano BBQ Grill That You Can Drive Around The Workshop”