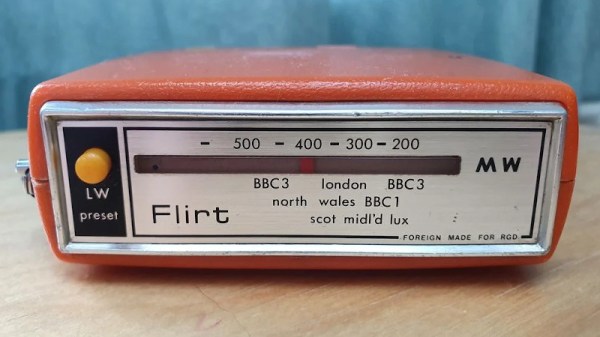

The invention of the transistor revolutionized radio, allowing receivers to be made far more compact and portable than ever before. In the middle of the 20th century, the devices exploded in popularity, and pocket transistor radios took the market by storm. [MisterM] had fond memories of such times, and when he found a 1970s Flirt radio at a car boot sale, it led to a cute little build.

The radio was stripped of its original hardware, with [MisterM] preferring internet radio to the terrestrial variety. In its place, a Raspberry Pi Zero was installed. This was fitted with a cavalcade of off-the-shelf modules to make it fit for pumping out the tunes. A Speaker PHAT was used for audio, while an Adafruit Micro Lipo board handled battery charging and a Pimoroni Lipo Shim served as the power supply. All this was bundled up inside the original casing.

The radio’s controls are a neat hack. The original volume and tuning dials were removed, sliced up, and glued onto two lever microswitches. This allows them to act as buttons instead. A new power switch was installed behind the original, and the Speaker PHAT’s LEDs were placed behind the tuning dial to act as a rudimentary display.

It’s a tidy build that repurposes an attractive vintage artefact into a device of the internet age, while remaining externally the same. [MisterM] has form in this space, with his vintage radio console build and video doorbell being particular highlights. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Vintage Transistor Radio Gets Internet Transplant”