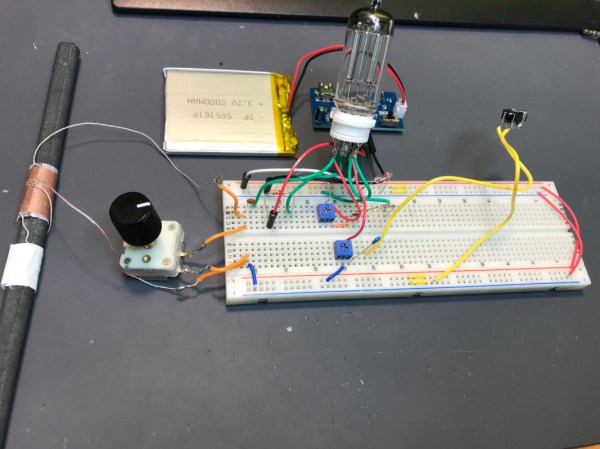

Coherers were devices used in some of the very earliest radio experiments in the 19th century. Consisting of a tube filled with metal filings with an electrode at each end, the coherer would begin to conduct when in the presence of radio frequency energy. Physically tapping the device would then loosen the filings again, and the device was once again ready to detect incoming signals. [hombremagnetico] has designed a basic 3D printed version of the device, and has been experimenting with it at home.

It’s a remarkably simple build, with the 3D printed components being a series of three brackets that combine to hold a small piece of plastic tube. This tube is filled with iron filings, and electrodes are inserted from either end. Super glue is used to seal the tube, and the coherer is complete.

The coherer can easily be tested by measuring the resistance between the two electrodes, and firing a piezo igniter near the tube. When the piezo igniter sparks, the coherer rapidly becomes conductive, and can be restored to a non-conductive state, or de-cohered, by tapping the tube.

Coherers and spark-gap sets are fun to experiment with, but be sure you have the proper approvals first. Video after the break.