When the USA entered World War Two, they lacked a powerful mobile communications unit. To plug this gap they engaged Hallicrafters, prewar manufacturers of amateur radio transmitters and receivers, who adapted and ruggedized one of their existing products for the application.

The resulting transmitter was something of a success, with production running into many thousands of units. Hallicrafters were justifiably proud of it, so commissioned a short two-part film on its development which is the subject of this article.

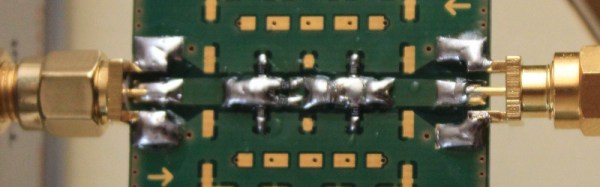

The transmitter itself was a very high quality device for the era, but even with the film’s brief insight into operating back in the AM era the radio aspect is not what should capture your interest. Instead of the radio it is the in-depth tour of an electronics manufacturing plant in the war years that makes this film, from the development process of a military product from a civilian one through all the stages of production to the units finally being fitted to Chevrolet K-51 panel vans and shipped to the front. Chassis-based electronics requiring electric hoists to move from bench to bench are a world away from today’s surface-mount micro-circuitry.

So sit back and enjoy the film, both parts are below the break.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Hallicrafters Goes To War”