Human input devices are a consumable on our computers today. They are so cheap and standardised, that when a mouse or a keyboard expires we don’t think twice, just throw it away and buy another one. It’ll work for sure with whatever computer we have, and we can keep on without pause.

On earlier machines though, we might not be so lucky. The first generation of computers with mice didn’t have USB or even PS/2 or serial, instead they had a wide variety of proprietary mouse interfaces that usually carried the quadrature signals direct from the peripheral’s rotary sensors. If you have a quadrature mouse that dies then you’re in trouble, because you won’t easily find a new one.

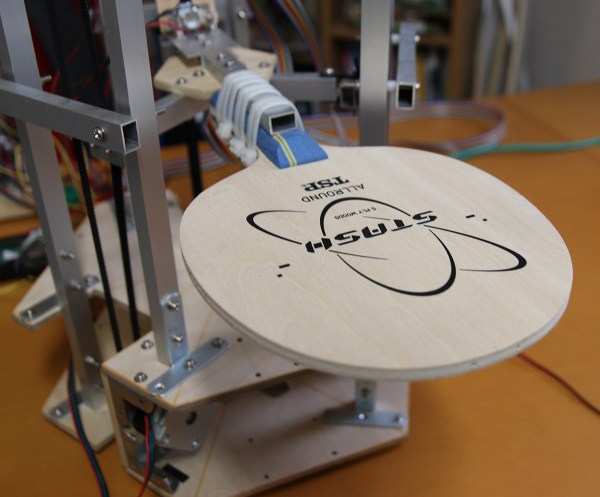

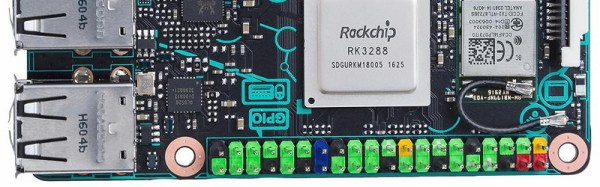

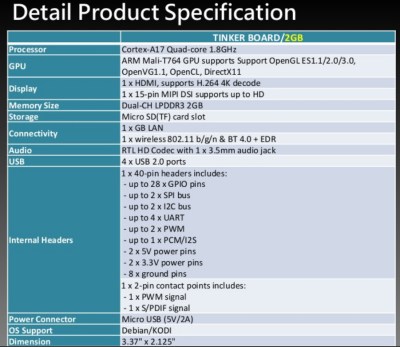

Fortunately there is a solution. In the intervening decades the price of computing power has fallen to the extent that you can buy a single board computer with far more than enough power to interface with a standard USB mouse and emulate a quadrature mouse all at the same time. This was exactly the solution [Andrew Armstrong] took to provide a replacement mouse for his Atari ST, he used a Raspberry Pi as both USB host and quadrature mouse emulator (YouTube link) through its GPIOs.

He’s put together a comprehensive description of his work in the video we’ve placed below the break, meanwhile if you’d like to have a go yourself you’ll find all you need to know in his GitHub repository.