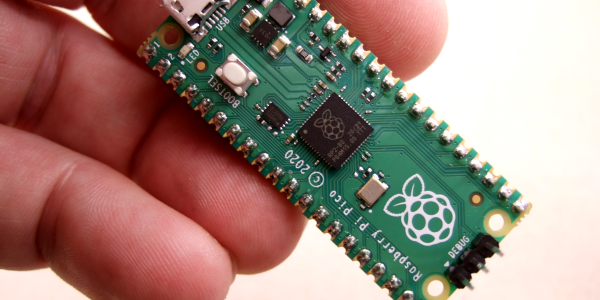

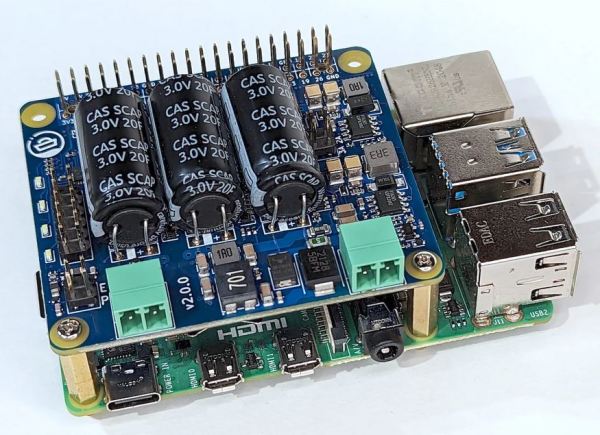

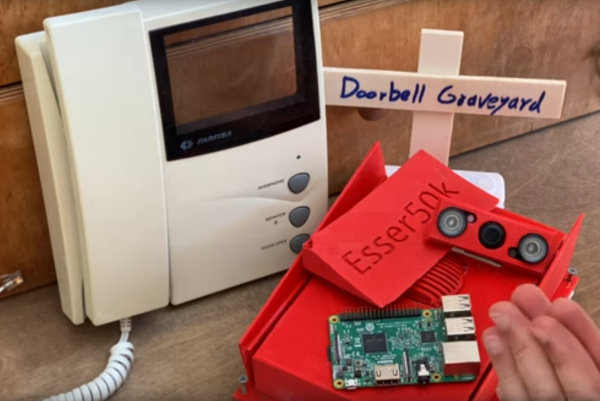

Essentially, it uses a Raspberry Pi and a Respeaker four-mic array to listen to conversations in the room. It listens and records 15-20 seconds of audio, and sends that to the OpenWhisper API to generate a transcript.

Essentially, it uses a Raspberry Pi and a Respeaker four-mic array to listen to conversations in the room. It listens and records 15-20 seconds of audio, and sends that to the OpenWhisper API to generate a transcript.The natural lulls in conversation presented a bit of a problem in that the transcription was still generating during silences, presumably because of ambient noise. The answer was in voice activity detection software that gives a probability that a voice is present.

Naturally, people were curious about the prompts for the images, so [TheMorehavoc] made a little gallery sign with a MagTag that uses Adafruit.io as the MQTT broker. Build video is up after the break, and you can check out the images here (warning, some are NSFW).

Continue reading “WhisperFrame Depicts The Art Of Conversation”